Visit Our Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

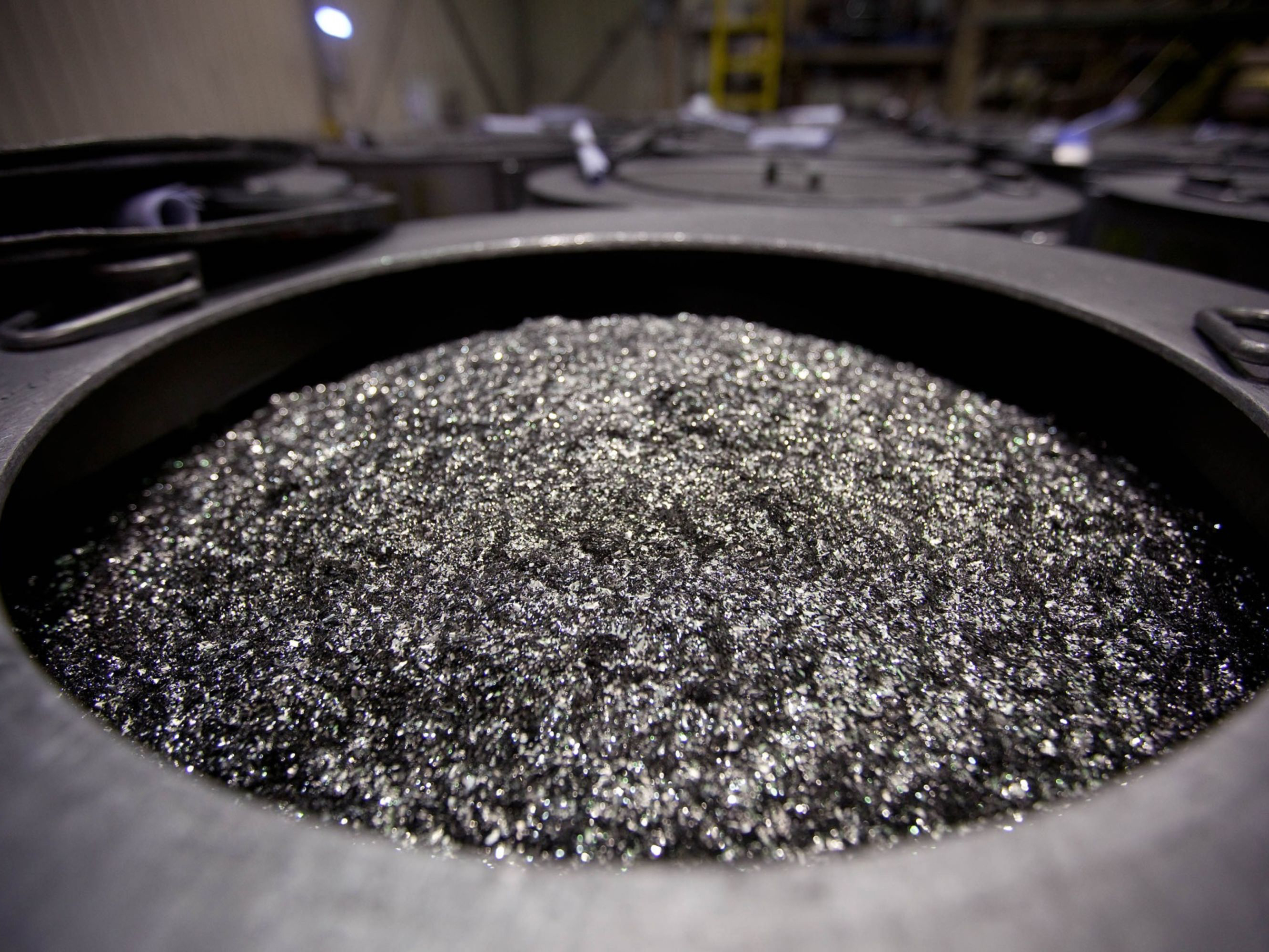

Efforts are underway in the U.S. to break China’s monopoly on the mining and processing of rare earth minerals, which are found in many high-tech products for consumer, industrial and military use. But it’s going to be a long haul to achieve that goal. In this conversation with SupplyChainBrain Editor-in-Chief Bob Bowman, Mark Chalmers, president and chief executive officer of Energy Fuels Inc., discusses his company’s efforts to process rare earths at a mill in Utah.

SCB: Where does Energy Fuels fit into the rare earth supply chain?

Chalmers: You're probably aware that it was only mid-April that we announced that we were going to enter the rare earth space. We think we're at a very unique advantage, mainly because of our White Mesa Mill in Utah. It is completely constructed and permitted to recover uranium and process uranium ores, and can produce both uranium and vanadium. With historical sources of monazite streams that contain uranium and thorium, we are ideally placed to process these at White Mesa to recover rare earths from those streams.

SCB: How many of the 17 rare earth minerals do you expect to find there?

Chalmers: I can't really answer that, because you may find them, but can you recover them commercially? If there are 17 minerals, how many of them are economically recoverable? But we think the distribution of monazite feeds is favorable to the heavies and some of the more valuable rare earths. We have a fully licensed facility, and since we announced we were going to enter the space, we’ve had Constantine Karayannopoulos join us as an adviser, and also Brock O'Kelley, who used to work for Constantine and Molycorp and is currently a professor at the Colorado School of Mines. Constantine was CEO of one of the most successful transactions in the rare earth business ever, when he sold the company he founded to Molycorp in 2012 for $1.3 billion. So we have a facility and two proven long-term earth professionals with a track record of profitable delivery joining our team.

SCB: The complete rare earth supply chain consists of four steps: mining, processing, metals and alloy production, and magnet manufacturing. Which of those are you participating in?

Chalmers: Right now we're mainly the second step, which is the processing stage. Our first step is to make an oxide concentrate that is uranium- and thorium-free, which can then be taken through further separation steps, by others or perhaps by our company. Our goal is to start off with the processing and removal of uranium and thorium, to come up with a concentrate that could then go to the next steps of separation.

SCB: And beyond that?

Chalmers: To move on to the separated products gets a lot more complicated and expensive. We think we're in a good position to take those next steps, but the first step is the concentrate. The monazite streams, with uranium and thorium, create issues for those who are trying to process it. There are streams of monazite right now, mainly from heavy mineral sand production in the world, in the United States, Southern Africa and Australia. There's one company in the world that I know of that is doing this right now — CNNC [China National Nuclear Corp.]. It’s taking monazite streams in China, removing the uranium and thorium, and producing a concentrate for the next steps of the rare earth separation process. CNNC's been doing it for a couple of years. We think we're in the same kind of box seat to do it in the United States. That’s why people like Constantine and Brock have joined us. Constantine is with Neo Performance Materials, which has projects in China, Thailand and Estonia. They're not in the mining business or the first step of rare earth processing — they produce separated rare earth products..

SCB: But when it comes to rare earths, who is taking the stuff out of the ground in the first place?

Chalmers: It’s our objective to receive rare earth ore and streams, mainly from mineral sands production, where they have a rare earth-bearing concentrate that also contains uranium and thorium. In a number of cases, they are currently sending it to China to do exactly what we would be doing at White Mesa. So our objective is to start off with modest production, to begin processing those concentrates in the United States. And because we can handle the radioactive products, we're in a good position to do that.

SCB: What’s your timetable?

Chalmers: We have an aspirational goal to be able to make commercial salable product within the next year. There's not a completely defined timeline. We think we can do it with largely existing equipment. We have all or most of the permits to do that at our existing facility at White Mesa.

SCB: When product leaves your facility, where will it go for further processing down the supply chain? Does it have to end up going to China, or can it stay in the United States?

Chalmers: There are a few emerging groups in the United States with plants that are looking at those next steps. There are other sites that could take that concentrate, including in China and Estonia. We haven't gotten that far to determining where does it go. The first step is to show that you can make a salable commercial product.

SCB: Others have announced similar plans in the past.

Chalmers: A number of people have said they were going to get into rare earths, and they've been doing this for 10 years. And they've never done anything at a commercial scale. We think we're going to have a shorter path than most people would think because of our head start with the White Mesa Mill.

SCB: When do you hope to start?

Chalmers: Subject to a number of things, we would like to be in a position where we can be producing modest commercial quantities within a year. There may be some additional capital investment required to ramp that up and make it more sustainable. But we think we have a good shot at demonstrating to the market that we can make a salable product at more than lab scale.

SCB: Are you optimistic that the United States can break China's monopoly over the rare earth supply chain?

Chalmers: History says we can do better. We can certainly improve our position on this substantially. Whether we completely break it, I don't know if I'd go that far.

RELATED CONTENT

RELATED VIDEOS

Timely, incisive articles delivered directly to your inbox.