Visit Our Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

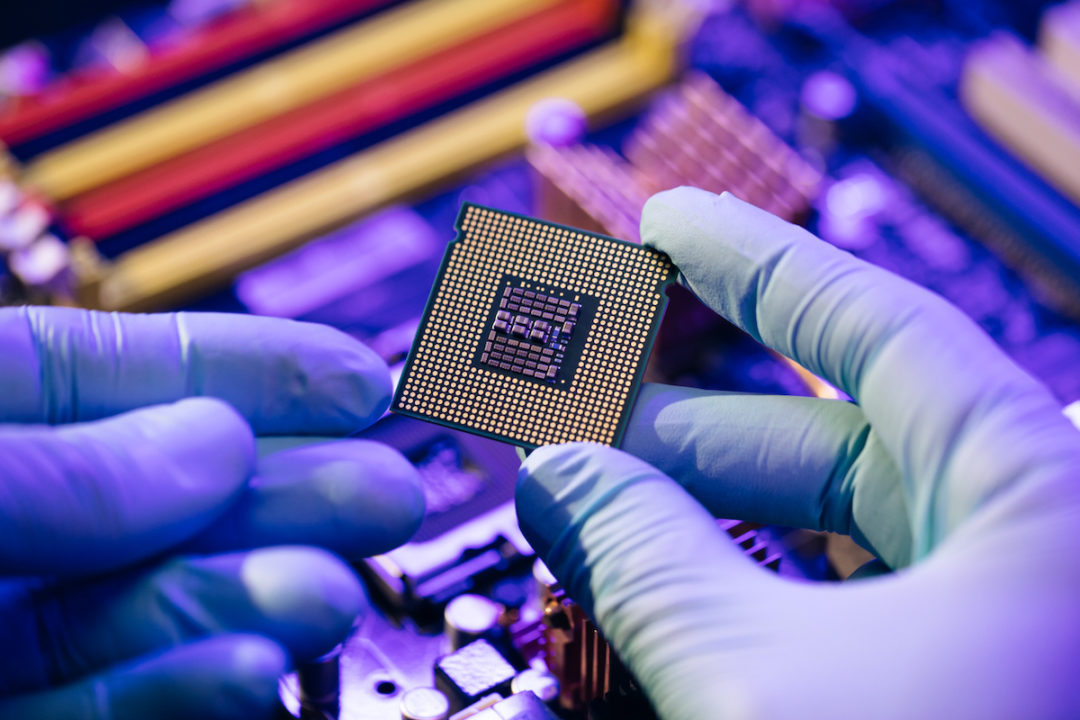

Photo: iStock.com/Mykola Pokhodzhay

Asia’s stranglehold on the global semiconductor market has caused a supply crisis for American manufacturers. The U.S. and European Union's dominance in semiconductor manufacturing disappeared in the mid-90s and early 2000s, when production moved overseas to major Asian countries such as Taiwan, Japan, Korea and China. To recapture that advantage and make the global technology market more competitive, western producers will need to drastically increase their domestic sourcing of semiconductors in the coming years.

What makes the technology so critical is the growing need for more sophisticated semiconductors with complex manufacturing processes, says Spencer Shute, principal consultant at procurement services provider Proxima.

More complex electronic devices, especially those found in electric vehicles, require more semiconductors. Yet production remains highly vulnerable to supply chain disruptions. That was demonstrated all too clearly when the COVID-19 pandemic caused widespread factory shutdowns in China and elsewhere in Asia. It was a wake-up call.

“The U.S. is trying to get back to being more self-sustaining,” Shute says, adding that American producers are equally concerned about the loss of intellectual property for chips that are used in military equipment yet produced in unfriendly nations.

Another worrisome concern is the possibility of China invading Taiwan, which currently dominates the global marketplace for sophisticated semiconductors. Taken together, these factors increase the urgency to bolster U.S. chip manufacturing capabilities.

In August of 2022, President Biden signed into law the CHIPS and Science Act, with the aim of lessening U.S manufacturers' reliance on China and other Asian nations, boosting competition, and stimulating innovation in the global semiconductor market. The act provides incentives in the form of tax breaks and federal grants, including $2 billion for legacy chip production and $13.2 billion for research and development, as well as job opportunities for American workers.

Progress toward that end in the private sector has been slow, but Shute says some organizations and government agencies have begun taking steps to prepare for the sourcing shift. Major multinational brands such as Samsung and Intel are among those to have announced plans to construct some 40 semiconductor plants in places like Texas, Oregon, New York and Ohio. “What we’re working on right now is getting that groundwork going,” Shute says. “But it takes time.” Companies and government agencies are still in the process of investing and establishing the necessary infrastructure, he adds.

Other countries are making similar efforts to boost domestic supply of semiconductors through government action. The EU, in particular, has been working to pass legislation similar to the CHIPS and Science Act. But it's been slow to improve its own semiconductor manufacturing capabilities. Shute says Europe's effort has been stymied by higher inflation rates across the continent, which have made it more expensive to build new plants.

“If I had to predict, I would say the U.S. would pull ahead of the EU [in domestic chip production],” Shute says.

Despite such efforts, it unlikely that the U.S., Europe and rest of the world will be able to completely sever trade ties with China. That’s because a lot of the raw materials used to make semiconductors — not to mention 21st-century technologies such as batteries for electric vehicles — come from Asia. “The U.S. is going to have to maintain some relationship with Asian countries, which is going to be a bargaining chip within those regions,” Shute says.

Although the U.S. is a long way from reestablishing a domestic supply of semiconductors, current research and development efforts, aimed at coming up with new ways to build chips, could “change the game,” Shute believes. The goal is to drive down production costs, increase innovation and possibly even become a net exporter of semiconductors.

Shute says the next three to five years will be key in getting the U.S. semiconductor sector back on its feet. And within 10 years, a majority of the country’s semiconductors could be produced domestically. “That’s a fairly lofty goal," he says. "But with the right innovations and investments, it can probably be done.”

RELATED CONTENT

RELATED VIDEOS

Timely, incisive articles delivered directly to your inbox.