Visit Our Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

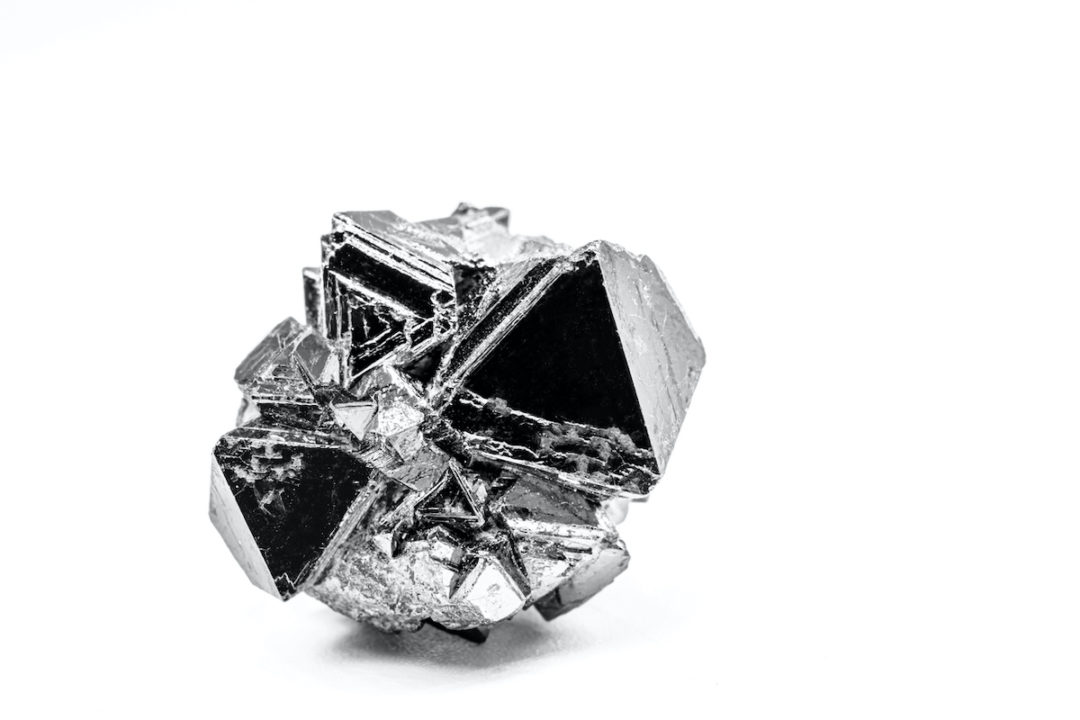

Photo: iStock.com/RHJ

The latest skirmish in the trade war between the U.S. and China provides yet another reminder of why American high-tech manufacturers need to diversify their supply of critical raw materials, including so-called rare earth elements (REEs).

Earlier this summer, China announced restrictions on the export of gallium and germanium, two metals used in semiconductors and electric vehicles. The action was widely believed to be in retaliation for the Biden Administration’s move to restrict exports of advanced semiconductors and chip-making equipment to China.

China accounts for around half of U.S. manufacturers’ supplies of gallium and germanium, and 94% and 83%, respectively, of the world’s supply. Further curbs by China on the export of critical minerals are likely, says Sandeep Rao, head of research with Leverage Shares, a provider of exchange traded products (ETPs), the prices of which are geared to the value of major commodities producers on exchange markets, calculated on a daily basis.

Also vulnerable to future export restrictions are 17 rare earth metals, of which China controls more than a third of global reserves, and an even greater share of current levels of mining and processing. While rare earth elements aren’t “rare” in a literal sense, China’s dominance of the global market, and the slow pace at which other nations are developing their own supply, make them so in practice.

The new restrictions on gallium and germanium — not technically rare earths, but equally essential in the production of high-end microchips used in defense systems and renewable energy equipment — are “basically a play against the U.S. deciding to limit the export of AI [artificial intelligence] technology to China,” Rao says.

The reasons behind China’s latest action might be economic as well as geopolitical in nature. Rao notes that supplies of critical minerals tend to outstrip demand. “There’s actually a glut of gallium and germanium in the market,” he says, adding that prices are down from the start of the year. Chinese restrictions could reflect a desire to stop selling those metals to the world at rock-bottom “cabbage” prices.

Despite dire warnings from U.S. industry and government about inadequate domestic supplies of critical minerals, “China doesn’t have a lot of leverage” in the long run, Rao says. For one thing, manufacturers stand to recover significant amounts of the metals through recycling. The process is already responsible for around 30% of annual supplies of gallium and germanium. “Imagine if you could go full scale [with recycling],” he says. “You would likely see a drop in mining and production.”

The same goes for many types of REEs, which are used in the magnets contained in headphones, to name just one application. Rao says there are “many thousands of tons” of old equipment lying around unrecycled.

“REE recycling is no longer just a choice, but it has become necessary in a world where resources are restrained,” wrote Stanford researchers Gorakh Pawar and Rod Ewing, in the journal of the Materials Research Society.

It’s no magic bullet, however. Recycling is a highly labor-intensive industry, Rao notes, making it unfeasible for siting in the U.S., absent some efficiency-boosting technology. Research toward that end is underway at MIT and Stanford, he adds, but the work awaits final publication of the results.

In any case, Rao sees a decline in the coming years in reliance on China for REEs and other metals. Vietnam, a late entrant in the market, is making significant strides in production. Australia already has a major mining industry up and running. And in California, the Mountain Pass Rare Earth Mine and Processing Facility has reopened after 20 years of inactivity, and currently supplies 15.8% of the world’s rare earth production.

Rao is bullish on the future of rare earth supply and development. “There’s always going to be a demand for REEs, and it has to keep increasing,” he says. At the same time, China’s recent actions on gallium and germanium are likely to serve as a wake-up call to high-tech manufacturers that have relied for many years on a single source for critical metals. Such materials are simply too important to be held hostage to the whims of geopolitics.

RELATED CONTENT

RELATED VIDEOS

Timely, incisive articles delivered directly to your inbox.