Visit Our Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The bots are coming. Are you ready? Photo: Helen Atkinson

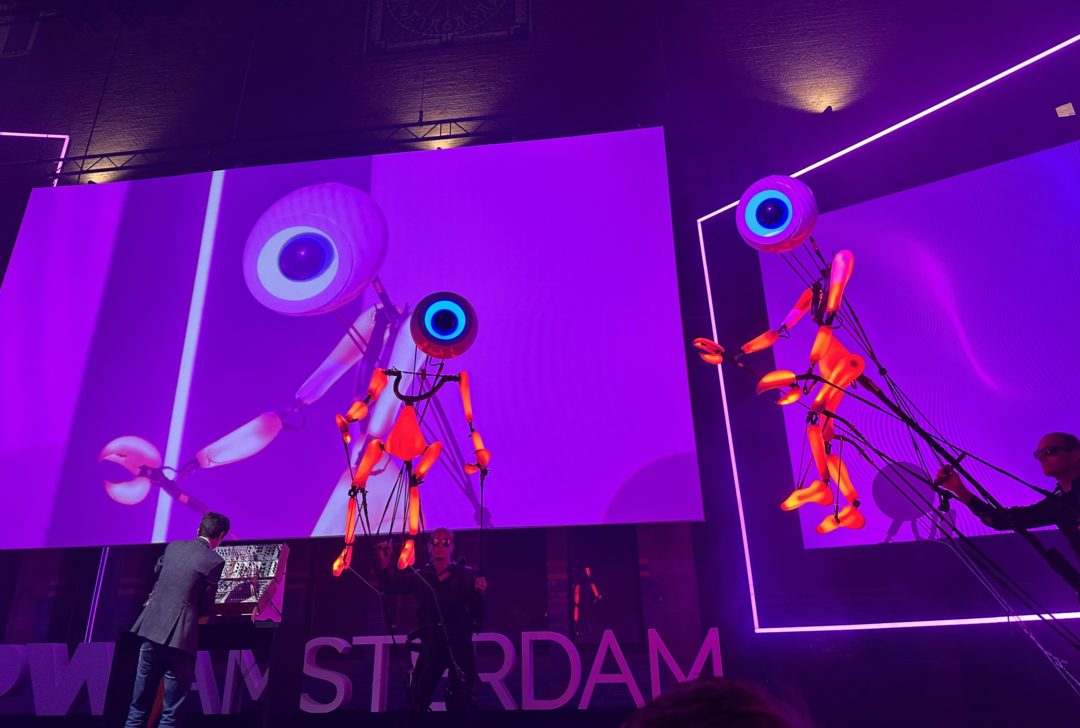

"Procurement used to be boring, but now we're rock stars. We run the company!" said Andrew Moskos, self-declared Number One Procurement Comedian, and host of the 2023 DPW Amsterdam procurement technology show in Amsterdam. During a dramatic opening ceremony October 11, where attendees were greeted with loud techno-funk and glowing, 10-foot-tall bot-puppets, founder Matthias Gutzmann, DPW's founder, said his goal was to "break procurement out of its silos, and create an end-to-end ecosystem."

What are procurement managers to do with this new-found recognition and power? Certainly, making smart use of existing and emerging technologies is one way forward – what’s often referred to as digital transformation. But many of the experts presenting at DPW23 warned attendees to remember that technology is only a tool. “Digital transformation is not about technology,” said David Rogers, a speaker at DPW 2023, a member of the faculty at Columbia Business School, and author of best-seller “The Digital Transformation Playbook," which has been published in more than a dozen languages. “Technology is the spur. The hard part is about the organization and the people, and how you design organizations so they’re able to adapt quickly at scale.”

Rogers, who has just published "The Digital Transformation Roadmap: Rebuild Your Organization for Continuous Change," was adamant that it’s not correct to think of digital transformation as a single shift, so that once you’ve achieved it, you’ll be done. “It’s wave after wave,” he said. “Digital transformation is not a project with a start and an end-date; it’s a continuous process.” Instead, organizations have to become more capable of adapting on an ongoing basis, he advised. The secret is to be willing to fail and to learn from those failures, Rogers said. He gave the example of the New York Times, which was one of the first major news publications to launch a website, in 1996. “A decade later, they were falling off a cliff because they were digitizing an old business model,” he said. After a major rethink, and a considerable amount of humility, the company arrived at a successful digital policy. “They got everything wrong until they got everything right.”

David Rogers. Photo: Helen Atkinson

David Rogers. Photo: Helen AtkinsonExperimentation is key, and that will mean failures. Rogers said it’s best to fail cheaply, fail early, and share the learnings – the last point being one of the hardest for companies to do, because humans tend to be embarrassed by failure. “When you’re trying a new thing, you’re not going to reduce the rate of failure. What you need to do is reduce the cost of failure,” Rogers said. “One of the biggest obstacles to change is prior costly failures. Everyone gets risk averse.”

A classic mistake companies make is to come up with a new idea and invest in it too heavily and exclusively – often under the aegis of a single senior executive. Instead, organizations should embark on a quest to find multiple solutions to a defined, specific problem, then stay flexible and open-minded. Oversight should be minimal – the green light for any project should come after a single meeting that is overseen by a board, not an individual executive, and the budget for each one should be a few thousand dollars, not millions, with a limited time-frame for proof-of-concept of 30, 60 or 90 days, tops. “Resource allocation should be iterative,” he said. “Then you shut down most of them and accelerate rapidly what works.”

In many ways, this is a scientific, rather than classic business, approach. “Managers look for data to prove their own beliefs; scientists perform experiments to prove themselves wrong,” Rogers observed.

In terms of procurement specifically, Rogers sees two great opportunities presented by emerging technologies such as generative artificial intelligence. First, tech-driven thinking can enable innovation and transformation across the business. “Procurement can slow down or speed up the business. It can get in the way and be a real roadblock, or it could be the opposite,” he said. Secondly, procurement managers need to make bold transformations in their own operations. “They need to blow up their own function,” Rogers advised. “Imagine if there were no procurement department in the company. What would be the problem that would be needed to be solved?” Getting your arms around that lessens the chance that someone will come along in five years with a technology that renders the functions of the procurement department obsolete, Rogers said.

The stakes are high, Rogers warned. “Most legacy companies are not adapting and changing,” he said. “Companies like Disney and John Deere are outliers.”

RELATED CONTENT

RELATED VIDEOS

Timely, incisive articles delivered directly to your inbox.