Total cost of ownership (TCO) was popularized by Gartner in the 1980s. The basic idea is that the value derived from a product involves more resources than what you pay the supplier. Take the modern-day smartphone. Why do you have one? Presumably to communicate, but there are many other uses it plays in your life, such as mp3 player, navigator, calculator and alarm. To capture that value, however, you’ll need not only to pay the cost of the device ($300-$1,000), but also service ($30-$100/month), insurance ($10-$20/month), case ($10-$20), and apps ($20-$100).

Figure 1

TCO is essentially a consumer-facing concept, but another term, total cost of acquisition (TCA), has more of a supply-chain and procurement application. In the past, it was less important in the U.S., as the nation gravitated toward free-trade pacts such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). That has changed under the current administration. In addition, because of automation and the development of manufacturing sites in other countries, TCA is regaining importance in the U.S.

Today, a manufacturer might have multiple choices of suppliers within overwhelmingly complex supply chains. How does the modern purchasing professional sort out which option is best?

Let’s break it down to three steps:

- What? Understand the supply-chain options strategically.

- How much? Populate the numbers for each assumption tactically.

- What does it mean? Quantify the total and understand where the costs are.

What?

Manufacturers spend a lot of time on value stream maps, a series of material and information flows within the factory. The modern purchasing agent should spend as much time on a supply-chain diagram (SCD) for commodities. The SCD is a simple mapping of raw and purchased materials, as well as custom-made parts, showing how the product comes together. The key at this stage of the analysis is to not care about specific numbers. We’re not worried about how much the supply chain costs, but who the players are, and what they’re adding to the value of the product.

Consider an electric motor. Figure 2 shows three possible ways that an American customer might set up its supply chain. Making an SCD is a fairly easy exercise, requiring no special tools — flowcharting or drawing software, Post-It notes, or a piece of paper will do. The SCD, along with a process flow diagram, are the first things that analysts should create, before thinking about finding a value for an assumption or calculating a number.

Figure 2

The SCD needs only to go deep enough to help make the decision for the business. In this case, it’s only necessary to go two tiers into the supply chain, without separately considering raw or purchased materials.

The SCD is great for uncovering hidden costs that the purchasing agent might not typically consider. Note, for example, the inclusion of export taxes and import duties. In the past, these costs might have been minor enough to exclude from consideration. However, in the age of big tariffs for countries such as China, it’s something that every purchasing agent should consider.

Drawing up a SCD allows planners to pull back from the proverbial trees, to see the forest as a whole.

How Much?

Once you have an SCD, you can populate a number for each element on the diagram. Presumably, getting quotes for materials and the value-add of each factory should be basic blocking and tackling to a purchasing agent. The logistics or supply-chain experts in your company should be able to provide you with shipping, warehousing and distribution costs.

Taxes and duties can be trickier. You can calculate them yourself by utilizing free resources, including HS Code look-up, the U.S. import duty page, and World Trade Organization tariff data. Another option is to ask the logistics or supply-chain experts in your company. If they don’t know the answer, they know whom to ask. There are plenty of external consultants and companies that specialize in this.

What Does It Mean?

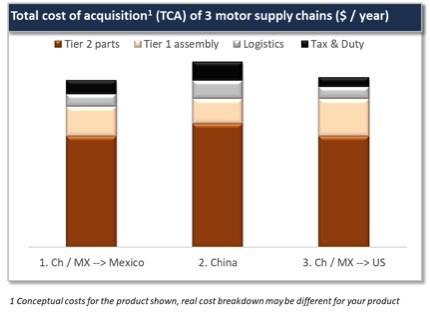

Now that you have an understanding of all the costs involved in your various supply-chain options from the SCD, and an estimate of each, you can add them up to understand your true total cost of acquisition. Looking at Figure 3, we can see that for our three possible supply chains, not only is the total cost different, but the cost breakdown is different as well. This insight can help companies design new supply-chain options for greater profitability. For example, sourcing more Tier 2 parts from Mexico not only reduces the piece-part cost, but also the logistics expense and taxes.

Figure 3

In this example, we’re assuming that all supply-chain designs have equal quality and delivery performance. However, this might not be true. For example, although the first supply chain is slightly less expensive than the third, it relies on assembly in Mexico. Is this geopolitical and extended supply-chain risk worth the small cost decrease? I’m not sure, but it’s a question that would have been harder to identify, had we not calculated the TCA.

Total cost of acquisition or ownership has always been the right way to evaluate an apples-to-apples comparison among supply chains. While manufacturing bases have become more global, some countries are moving away from a free-trade paradigm to one that’s built around traditional import tariffs and duties. This means that purchasing professionals can no longer ignore the implications of tariffs on TCA. By using an SCD to understand the cost of each supply chain options, a confusing and murky calculation can become a clear analysis to highlight opportunities for profit.

Eric Hiller is managing director of Hiller Associates.