A recent study touts the “smart” factory as a magic bullet that can solve any number of manufacturers’ problems, from low productivity growth to uncompetitive operations.

In the spring of this year, Deloitte and the Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation (MAPI) surveyed more than 600 executives of U.S.-based manufacturing companies about the impact of smart factories on their organizations. Their conclusion: Smart factories promise to be a “game changer” for American industry, resulting in a tripling of productivity improvements over the next decade.

The effort, of course, raises a key question: Just what is a “smart” factory? It’s more than a question of employing advanced technology with quality-sensing and detecting equipment, says Paul Wellener, vice chairman in charge of Deloitte’s U.S. Industrial Products Construction Practice.

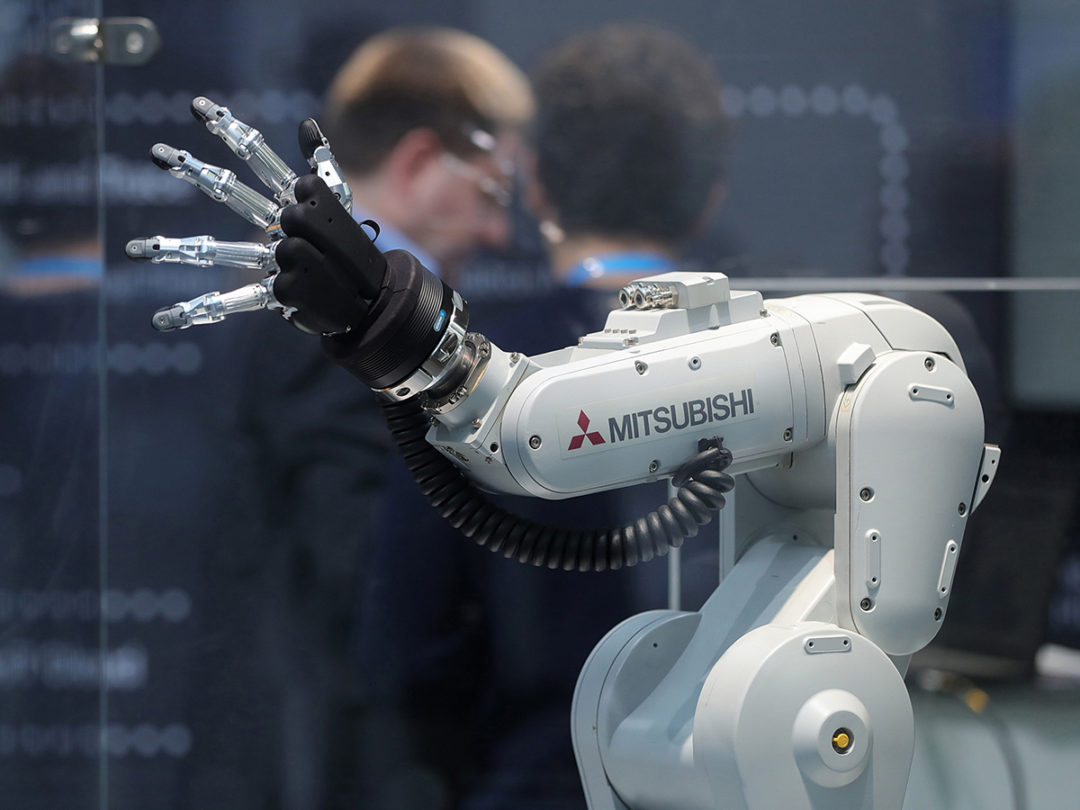

To make the leap to a smart factory, manufacturers need to incorporate multiple elements of cutting-edge technology, such as analytics, the internet of things (IoT), smart conveyance systems, cloud computing, artificial intelligence and augmented or virtual reality — all elements of what’s being called the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

The companies surveyed by Deloitte and MAPI are in varying stages of that journey. The report identifies three categories of aspirants, based on their current level of progress: trailblazers, made up of rapid implementers of the latest technology (account for around 18% of the total sample); explorers, open to experimenting but not yet willing to commit fully to the initiative (55%); and followers, who “are waiting for things to be proven out” (27%).

The leading group saw a 20% increase in factory capacity utilization when implementing smart technologies, while explorers and followers together experienced an 11% improvement. (Even followers have adopted aspects of smart systems, Wellener notes.)

Additional improvements on the factory floor were seen in the form of higher labor productivity (19% for trailblazers and 12% for the other two groups), and production output (18% for trailblazers and 10% for the rest).

Trailblazers further distinguished themselves by devoting more resources to smart technologies — roughly two-thirds of their manufacturing budgets, versus around 30% for explorers and followers.

Specific applications of smart technology included robotics, automation hardware and software, active sensors, IoT, vision systems, edge computing, wearables, blockchain and virtual and augmented reality.

The survey authors view smart factories as the key to jumpstarting what they view as sluggish performance by U.S. manufacturers over the last two decades. Productivity growth in that sector, they observe, “appears stuck.” Between 2007 and 2018, it registered an average of just 0.7%. And over the last five years, it has shown a net average growth of zero.

Smart factories, the survey says, are needed to turn that trend around. “The smart factory could potentially ignite stalled labor productivity and unlock the key to productivity for manufacturers,” it says. In all, it identifies 12 common categories of use cases, employing a combination of modern technologies to boost results. (The majority of manufacturers with active investments in smart factories are running an average of nine use cases, the survey finds.)

Among the hypothetical cases cited in the survey is “Kentucky Pumps & Valve Co.” Faced with an unacceptably high rejection rate for its graduated flow valves, the company installed vision system that deployed cameras, edge computing and AI. It drew on a partner’s pre-existing data models, which were able to train the new system in less than a week. The edge servers enabled real-time image processing, with immediate detection of defects on the line. As a result, the production of defective pieces was cut in half, the overall rejection rate dropped to within 3% of the threshold, and productivity rose by 50%.

Given the impressive results from actual manufacturers’ move to smart factories, one might wonder why more don’t make the effort. Wellener chalks it up in part to a lack of vision and long-term strategizing. “Do they view these capabilities as a fad, or the way of the future?” he asks.

Progress might also be slowed by failing to have the right talent on hand to meet the technological challenges that come with implementing smart-factory initiatives. Wellener stresses the importance of having support from all levels of the organization — IT, factory operations, finance, steering committees and the CEO. A successful effort, he adds, calls for “heavy doses of communication, and measuring results to demonstrate business benefits.”

Newcomers to the technology might well balk at the cost of entry, but Wellener dismisses that concern. Leaders who invested 65% of their budgets in smart capabilities didn’t experience an overall increase in spending, he says. “They changed from spending money on old tech to new tech.” What’s more, the retrofitting of existing equipment with smart sensors can be relatively inexpensive.

Wellener believes smart factories are the solution to the growing skills gap in American manufacturing, which is expected to see 2.4 million jobs go unfilled over the coming decade, due to retirements and the industry’s unattractiveness to younger workers.

“We’ve got a war for talent going on in our country,” Wellener says. “It’s not about cost reduction. It’s about how I get my manufacturing capabilities in the right place.”