American companies across the board are striving to reduce their dependence on China as a source of manufacturing, but one industry sector is especially keen to bring production back to the U.S.

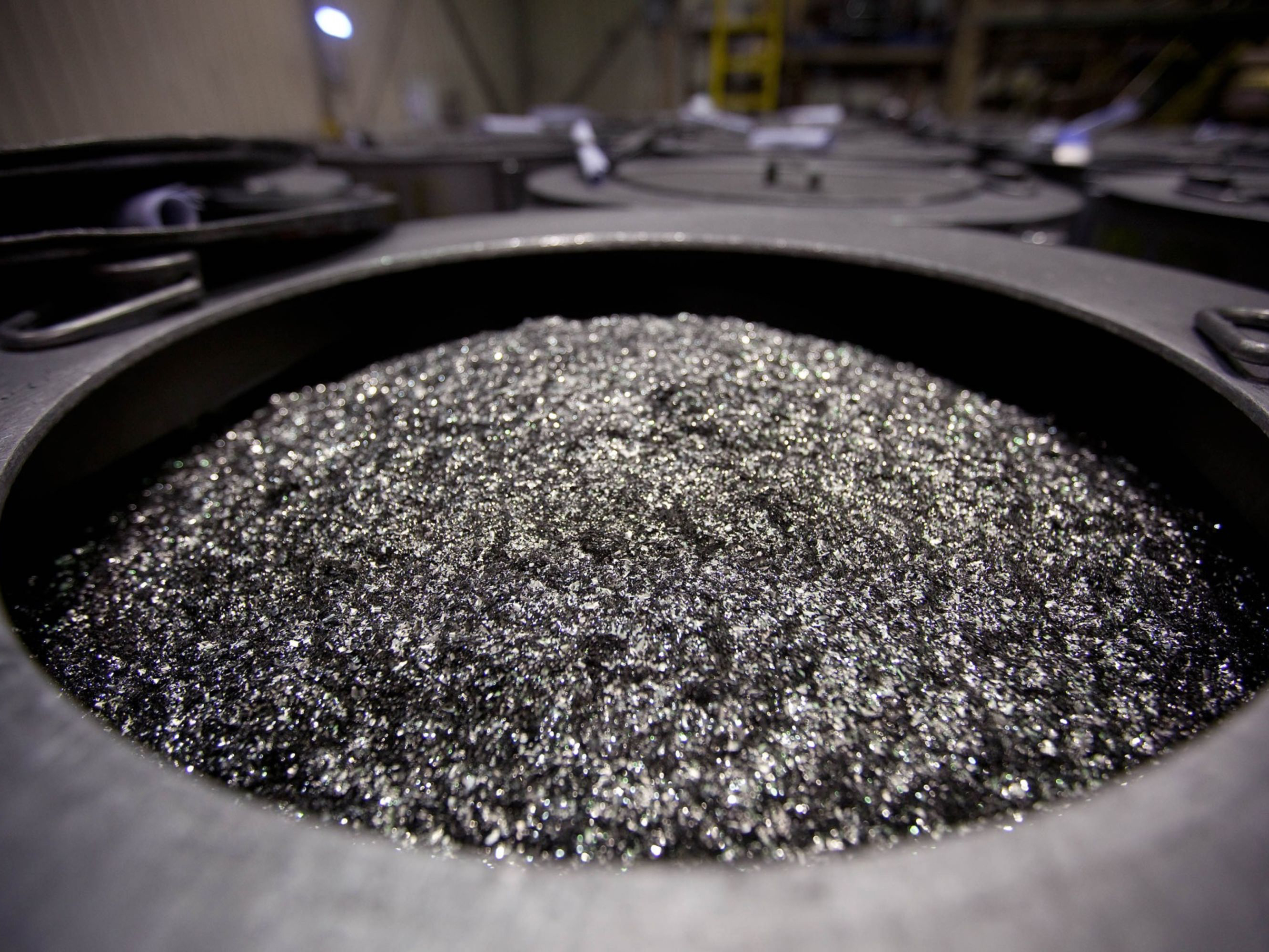

It’s the business of mining and processing rare earth materials, 17 chemical elements that are essential to the making of many high-tech products, from computers to electric cars, wind turbines and military hardware.

China currently commands a near-monopoly on the production of rare earths, which are only “rare” in the sense that no other country has wanted to take on the cost, production complexities and environmental consequences of extracting them from their native soil.

It wasn’t always so. From the 1950s through the 1980s, the U.S. was the dominant world producer of rare earths, according to Dan McGroarty, advisory board member of USA Rare Earth LLC, a venture that has invested in the development of Round Top Mountain in West Texas. (The mining site holds substantial deposits of critical rare earth and high-tech metals, including lithium, uranium and beryllium — in all, 16 of the 17 classified elements.)

The days of domestic production in the U.S. were mostly before the age of microcomputing. Now, of course, technology has advanced to such a degree that rare earths are more critical than ever before. But in the late 1980s, at the conclusion of the Cold War, the U.S. backed away from rare-earth mining and production, as manufacturers turned to global sources of raw materials. China, meanwhile, took the long view, moving to amass both commercial and geopolitical power by controlling nearly 97% of global rare-earth production.

Since then, there have been abortive attempts to restart domestic operations in the U.S., most notably by MolyCorp Minerals LLC, owner of the Mountain Pass Mine in California’s Upper Mojave Desert. That project sputtered due to serious environmental concerns raised by an explosion in the 1990s of a pipe carrying radioactive wastewater, and subsequent financing difficulties during the Great Recession of 2008.

Now, USA Rare Earth wants to loosen China’s grip on those essential materials by bringing some mining and processing capability back to the U.S., to a degree that hasn’t existed previously. According to chief executive officer Pini Althaus, the rare-earth supply chain actually consists of four distinct stages: mining, processing, metals and alloys production, and magnet manufacturing. (Rare-earth magnets are the strongest magnets made, found in such products as computer hard disk drives, medical devices motors, bearings and wind-turbine generators.) USA Rare Earth wants to perform all four of those steps within U.S. borders, something that has never been done before.

The Round Top project takes care of the initial mining stage. For processing, USA Rare Earth has opened a facility in Wheat Ridge, Colorado. For magnet production, it recently purchased the equipment of a manufacturing plant in North Carolina, formerly owned by Hitachi Metals America, Ltd. The company is now reviewing possible places to relocate the magnet operation, where it expects to turn out at least 2,000 metric tons of rare-earth magnets each year, or around 17% of the current U.S. market.

That leaves only stage three, the production of metals and alloys. McGroarty says USA Rare Earth is reaching out to companies that have had relevant domestic operations in the past — “people who are in that space, to see whether it can be revived.” In the meantime, it’s building both upstream and downstream capabilities, as it pursues a “mine-to-magnet” strategy.

The company doesn’t expect to surpass or even approach the level of rare-earth production in China. Last year, the U.S. purchased 12,000 metric tons of rare-earth magnets, or around 6% of the global market. If it maintains that level of buying, the country’s annual purchases will increase by more than 7,000 metric tons by 2027. USA Rare Earth is hoping to supply at least a portion of that product domestically.

“If we can make a dent — producing 10% to 20% of materials on par with China, the U.S. government and defense [sector] would be able to source from a domestic mine,” Althaus says.

The dream is still some ways off from becoming reality. Once USA Rare Earth decides where to locate the magnet facility, it will take about a year before processing can begin. And Round Top will need around 30 months to reach full production.

The company is betting that its efforts will be aided by a newfound awareness of the need for domestic sourcing, both in the private and government sectors. “Developing a full rare-earth supply chain independent of China is essential for both the national economy and national security,” said Gen. Paul Kern, U.S. Army (ret.), a board member of USA Rare Earth.

Adds Althaus: “We’re looking to create a very viable alternative for the U.S. to have its own critical materials supply chain.”