The global pandemic has exposed the utter dependence of the U.S. and the world on China for critical equipment and raw materials. That’s especially the case with the supply of rare earth elements (REEs), which are required in numerous commercial products and defense systems. The risks of China asserting tight control over REEs have been well-documented, and COVID-19 has served only to underscore them once again.

Unfortunately, current market structures, based on the lowest cost of production, can’t overcome China’s dominance in REE because of national strategy, vertical integration and industry subsidies.

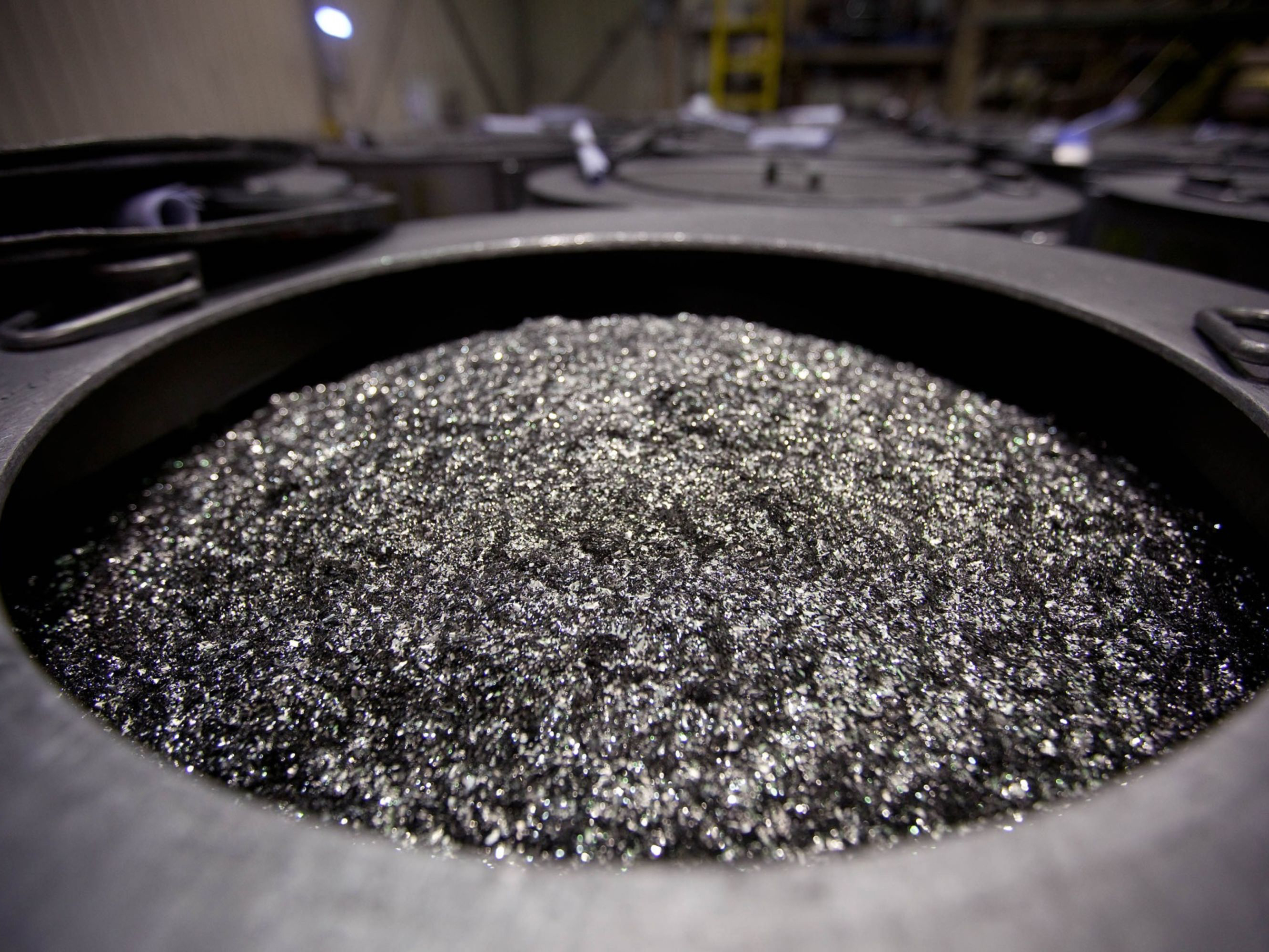

REEs consists of 17 elements in the third group of the periodic table. China produces an estimated 132,000 metric tons annually, with estimated reserves of around 44 million MT. Figures for the U.S. are around 26,000 and 1.4 million MT, respectively. REEs are widely used in many commercial high-tech products, such as smartphones, TVs, batteries, medical devices, and defense weaponry.

China’s industrial policy prioritized the support and development of its rare earth industry as a national economic and security initiative. It included three aims: control the REE supply chain, capture western intellectual property, and embed its materials into U.S. commercial and defense systems. Companies such as General Electric, Northrup Grumman and Boeing lack the capability to process REE oxides into usable components. Currently, almost all REEs mined outside of China are shipped there for processing into high-value metals, magnets and alloys.

China’s national strategy provided small-business subsidies to vertically integrate the high-tech supply chain. The country’s Belt and Road Initiative has further advanced that strategy by acquiring foreign assets on loan defaults, purchasing in-country REE mines to offset country export quotas, supporting local technology, and targeting IP through collaboration with foreign academia and research institutions.

The 1980s saw a drastic reduction of REE mining in the U.S. China acquired technology from General Motors that allowed it to move from a low-end material supplier to a producer of magnets, alloys, and metals. In the process, it was able to eliminate competition and dominate world supply. The U.S. essentially ceded capability and control to China, through lack of a coherent defense or administration policy that would have recognized REEs as critical to the economy and national security. It wasn’t until 2019 that the U.S. Department of Commerce outlined six key areas of a federal strategy for ensuring the domestic supply of critical materials.

Through the lack of a sustained and aggressive policy toward domestic development, the U.S. ignored the potential for a collaborative public-private partnership model that could restore the country’s leadership in REE sourcing and fabrication.

In addition to low labor costs, China achieved effective price controls by subsidizing small-market REE organizations, manipulating local and world events through restrictions on exports to Japan, idling domestic plants to reduce over-supply, and securing overseas sources via acquisitions, the Belt and Road Initiative, and political influencing. With a near-monopoly in REE sourcing and labor costs, China’s current pricing posture makes it nearly invincible — unless the U.S. adopts a different way of thinking.

There’s a prevailing belief in the U.S. that private investment and the opening of new domestic mines will solve the nation’s resource problem. This is not the case for the following reasons:

- The introduction of new material availability will lead to a lowering of prices and affect mine operations, most drastically in advanced economies, due to large initial investments and higher operating costs. The bankruptcy of the American mining company Molycorp is a prime example. REE- producing mines take an average of more than five years to become fully operational. By that time, that initiative might no longer be viable, due to price decreases from new capacity, global pricing pressures, or other reasons. Only if market prices remain above the entry price will new mining operations be sustainable. However, further processing and fabrication of the ore into value-added alloys and metals will require additional plant installations with higher cost. It’s obvious that this model has failed since the 1980s.

- China can manipulate new capacity by further lowering its prices and increasing supply, temporarily absorbing losses to eliminate new for-profit companies. It was highly effective in reducing REE exports in 2010, and has explicitly warned the U.S. that it will cut off REE supplies as a countermeasure in the ongoing trade dispute between the two countries.

- REE ores continue to be shipped to China for processing into value-added materials, alloys, and finished goods. This is solely due to the low-cost, market-efficiency philosophy being followed blindly by the U.S. at the expense of its own national interest. While China gains strategically and financially by controlling the value-added REE supply chain, the U.S. continues to forego a potential national strategic lever by sticking to old models.

- China continues to dominate global supplies of REE, force value-added domestic manufacturing, and capture IP in return for allowing foreign businesses into its markets. In 2017, it enacted a cybersecurity law requiring network operators to store select data within China, and allow Chinese authorities to conduct spot-checks on companies’ network operations. The law has raised concerns among foreign businesses over tighter data controls, increased risk of intellectual property theft, and forced switching to Chinese-made equipment.

Attempting to wrestle REE supplies from China solely by opening new standalone mines will only further erode the United States’ economic and national security. A private-public partnership supply-chain model is needed to break this critical dependency.

(Note: This is the first of a multi-part series of articles.)

Shubho Chatterjee is a digital transformation, strategy, technology and operations executive.