President Biden far surpassed his original goal of administering 100 million doses of the COVID-19 vaccines within his first 100 days in office, having met that mark by day 58. But the Administration’s initiative couldn’t have succeeded without a substantial manufacturing and logistics infrastructure backing it up.

For all the inevitabilities of Murphy’s Law, the nation’s manufacturing base was already exerting “unbelievably good control” over its supply chain, from material sourcing through delivery, before Biden made his ambitious pledge, says Sean Riley, vice president of global industry solutions with Software AG. And subsequent to that, industry was able to gear up strong manufacturing practices that allowed many companies to pivot from production of everyday materials to those considered essential for pandemic response.

Companies producing the vaccine displayed a remarkable level of cooperation. When Johnson & Johnson encountered snags in its own manufacturing schedule, it struck a licensing deal with Merck & Co., Inc. to make additional drug substance, formulate and vials of the J&J vaccine in the U.S.

Production outside the country was vital to meeting American needs for the vaccine. In fact, the vast majority of doses were manufactured outside the country, says Riley. That said, there were significant challenges in getting the vaccine to market. “If you did a complete post mortem, you’d find that it looked more like a duck above the water,” he says. “Underneath the water, its feet are paddling like crazy.”

Crises tend to elicit action. In the case of COVID-19, “heroic efforts” by manufacturers and producers were likely made possible by the short-term nature of the project, and the urgency of a response to the rapidly spreading coronavirus. “I don’t think it’s necessarily possible to make those transitions on a long-term basis,” says Riley.

He recalls working at a company that was undergoing an enterprise resource planning (ERP) software implementation — not, of course, a matter of life and death like the vaccination effort — in which logistics and customer-service coordinators were temporarily sleeping at the office to get the job done. “They did it, and came out the other side, but you can’t sustain that.”

Logistics and distribution of the vaccine were for the most part highly efficient, at least until it came to the last mile. Three basic models were followed, according to Riley: single pallets of cooling boxes, keeping the vaccine at the proper temperature and mostly conveyed around the world by air freight; pallets or multiple cooling boxes passing through a cross-dock facility, then moving on to final delivery; and the breaking down of medications into single doses to various locations. The chosen method depended on the size of the receiving facility, and its ability to receive trucks and store inventory on site. A big-box store such as Costco might accept full pallets, but a neighborhood CVS or Walgreens pharmacy can only handle smaller and more frequent shipments.

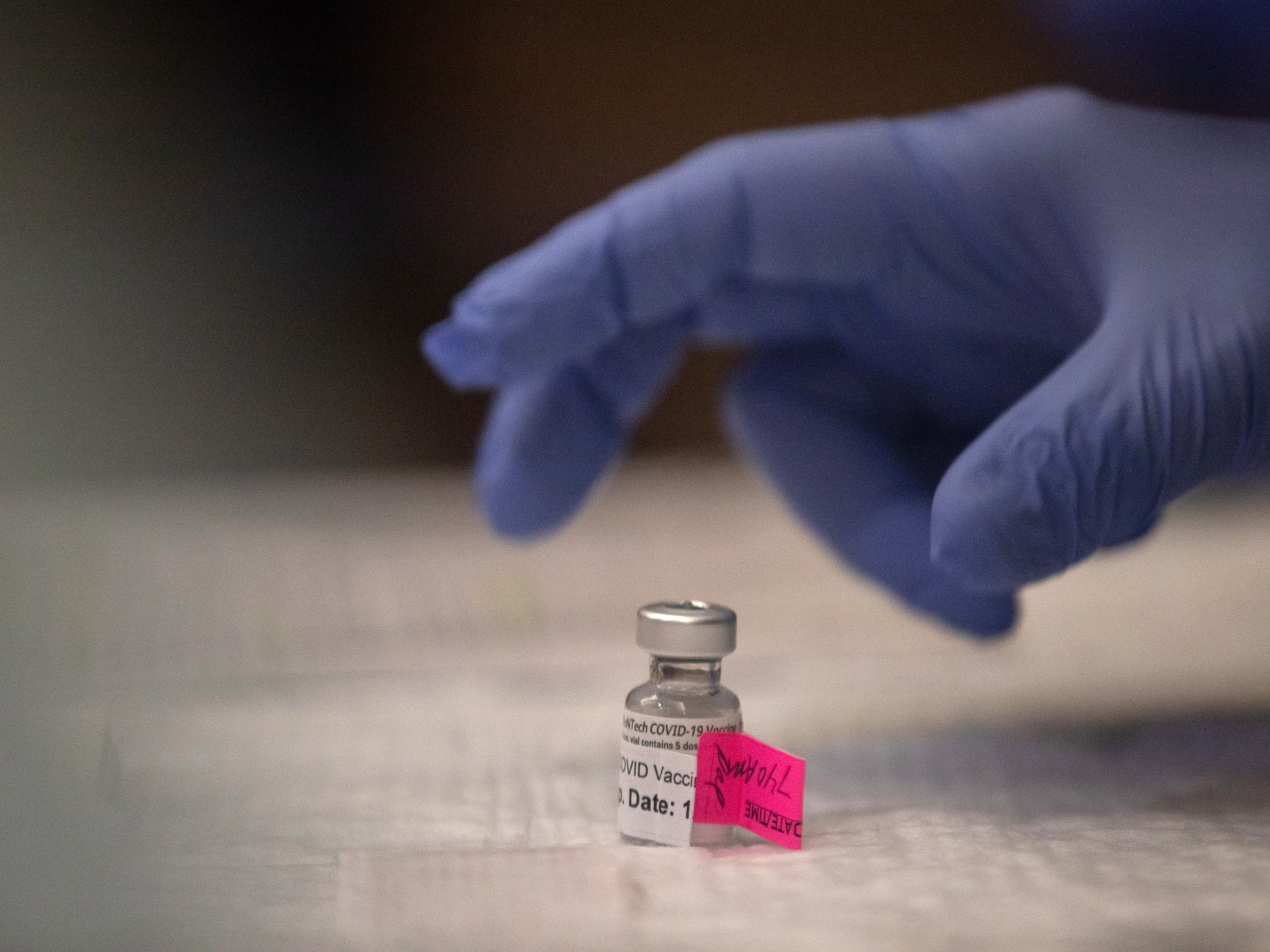

It was in the last stage of delivery that distributors encountered the most problems, although receivers were able to work out some creative solutions, such as grocers deploying existing cold-chain capabilities for keeping the vaccines chilled. (Those produced by double-dose manufacturers such as Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna require far colder temperatures than are needed to keep food safe, but were still valuable for short-term storage, Riley says.)

In the midst of the distribution effort came severe winter storms that slowed delivery and shut down clinics throughout the Midwest and South. But Riley says such disruptions pose no surprise to parcel-delivery experts such as FedEx, UPS and DHL, as well as specialized medical couriers. “They can be managed and dealt with, with equipment moved and re-optimized for when roads will be traversable again.” Moreover, “logisticians are prepared for such events and understand how to tackle them. They have playbooks in place.”

No such playbooks existed, however, when it came to informing the public about where, when and for whom vaccine doses were being administered. On the contrary, confusion often reigned, with people frantically trawling websites for last-minute notifications of availability.

“I lay that squarely at the feet of federal, state and local governments,” says Riley. “In my opinion, their chain of communication is not great.” The number of doses available to a given community “bounced around,” with allocations continually being rebalanced in a manner that was driven more by political considerations than the principles of supply planning, he says.

What lessons can be learned from the experience for the future? “I don’t think it will go back to normal,” Riley says, adding that considerations of risk are now front and center for most organizations, even if that means spending more on buffer stock and other anticipatory measures.

“Before, supply-chain risk was something you talked about every so often,” Riley notes. “It wasn’t something that was part of continuously evaluating the supply-chain network. Now, because of the pandemic, while the focus on cost isn’t going away, there’s going to be significantly more emphasis placed on risk as well as agility. How fast can I shift my supply chain to specific issues that might occur? How resilient am I to disruption? Companies are going to take a hard look at how to reconfigure their supply-chain networks to make sure they have the best cost at an acceptable level of resiliency, to ensure a more robust supply chain.”