Visit Our Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tom Mathew travels most weeks from his home in London to the industrial park on the edge of the northern English town of Bury from where the family business distributes food and drinks to schools and hospitals.

It takes just over two hours by train to go the first 160 miles (259 kilometers) to the nearby city of Manchester. Usually, there’s even wifi so he can get some work done. The trip will be quicker once a controversial new high-speed rail link is completed, albeit in two decades.

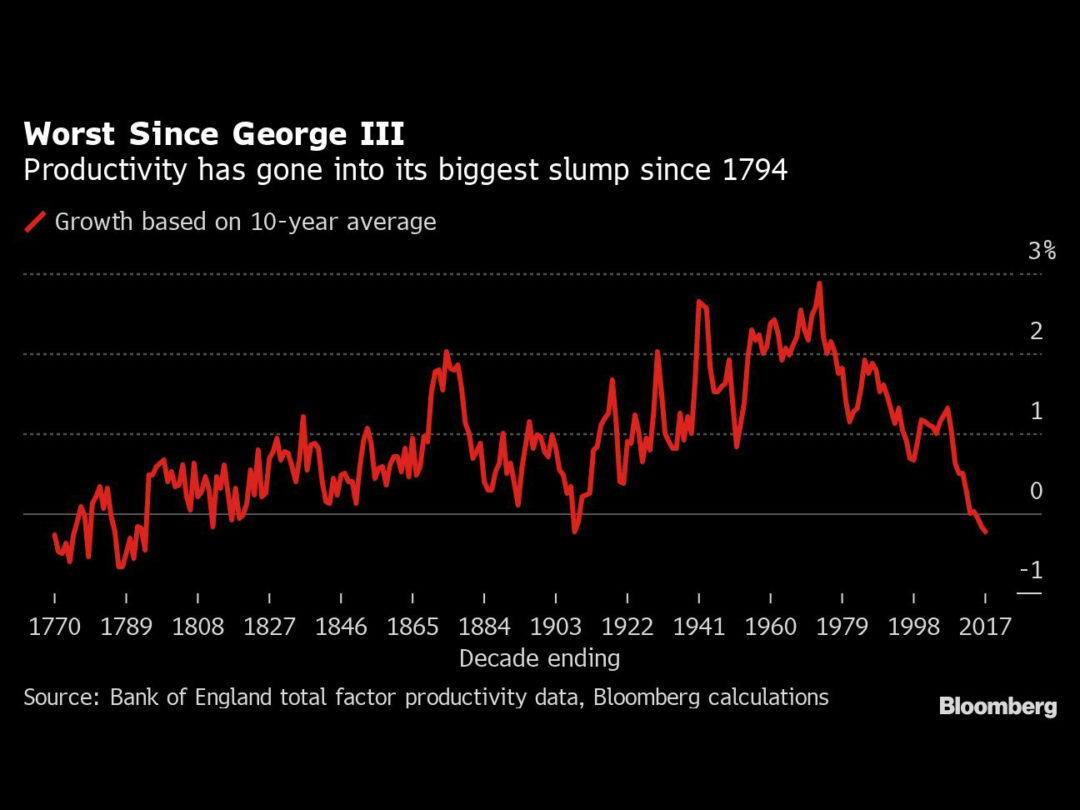

Then Mathew, 33, begins a completely different journey, one that exposes the underlying malaise in the economy: the weakest productivity performance since the Industrial Revolution. It’s something the government must contend with just as the U.K. enters a critical juncture after leaving the European Union and tackles the coronavirus outbreak.

In an all-too-familiar account of Britain outside the big cities, Mathew’s next dozen or so miles require either a taxi or a combination of tram and bus that can add another hour again. The poor infrastructure hampers the company’s ability to attract staff because too many simply can’t get to work on time. One employee commutes from a town 30 miles away and it can take more than two hours by car or train. Road congestion regularly delays deliveries.

“They seem to be obsessed with huge projects, headline grabbers, when actually the question is could they be doing more around how much businesses our size make up of the economy,” says Mathew. “If you can improve the productivity of those companies, you’re going to improve the productivity of the whole country.”

The fact that the British spend more time than just about any developed nation for the same economic benefit presents the biggest challenge to a government aiming to make the country a powerhouse outside the EU — with or without a trade deal with the bloc.

Poor productivity is the slow puncture that has curtailed economic growth potential to just over a third of the government’s 2.8% target and left companies at bottom of the league table for efficiency of output. The government’s task is also made tougher by the huge disparity between London and anywhere more than an hour north.

A report by the Office for National Statistics on Feb. 29 showed an hour of work in London produced 44% more gross value to the economy than the northwest or a whopping 76% more than the part of the Manchester metropolitan area that includes Bury. Productivity there is lower than it was in 1994.

“Leveling up” the country has become the mantra of Prime Minister Boris Johnson after so many voters in northern regions abandoned their traditional politics and defected to his Conservative Party in December’s election as he promised to “Get Brexit Done.”

This week’s budget is expected to deliver billions of pounds of infrastructure spending based on a review of the government’s “Green Book,” the guidelines for projects. Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak will also address on Wednesday the potential impact of the latest global headwind, coronavirus.

“We are on the verge of a Japan-like decade of stagnation if we can’t transform productivity,” says Tony Danker, chief executive of Be the Business, a group that aims to boost U.K. competitiveness. “This is the secret sauce missing in the economy that will fuel growth.”

Bury, population 80,000, is one of the red-brick northern towns that encapsulates Britain’s Victorian heyday and the challenges the country now faces. Geographically, it’s in a prime spot in the shadow of Manchester, the city that defined the Industrial Revolution. The railways arrived in Bury in the 19th century, as did a hallmark of English life at the time, a local soccer club.

While the town is one of the lucky ones — it maintains its connection to central Manchester via the city’s tram network — it suffered from cuts after World War II as local industry went into decline. The only trains moving through Bury now are the historic steam and diesel engines that operate on the rescued heritage line. Bury Football Club was expelled from the soccer league last year because of financial trouble.

“This is the country that brought railways to the rest of the world,” shrugs volunteer John Hulme as he stands in the entrance to an old disused station, which now houses displays of bygone engines and signage from long-abandoned train stops.

The government’s spending plans include 100 billion pounds ($128 billion) on the HS2 high-speed rail network from London, even though it probably won’t reach Manchester until 2040. By comparison, new local bus and cycle networks to ease congestion on roads are slated to get just 5 billion pounds. A proposed east to west northern train line that could more than double average train speeds has yet to be approved.

But it’s those kind of smaller, more locally targeted initiatives that Mathew and his sister and business partner, Hannah Barlow, say would make a bigger difference to productivity — or, as they see it, efficiency and profitability.

Their business, Dunsters Farm Foodservice, was built up over 60 years from their grandfather’s milk deliveries. It needs to get vans out from the 20,000 square-foot warehouse to schools before parents drop off their kids, something again Barlow blames on a lack of alternatives. Shifts run from 4 a.m. to 11 p.m., in part to take traffic into account.

“With the northern archaic system, everyone just jumps in a car and that does have an impact on our deliveries, our stock,” says Mathew.

To get more done for the cost, they have focused on technology, streamlining the process by which orders are picked from the warehouse and replacing paper lists with management software. That reduced the time employees spend walking around the vast floor space by as much as 40% and has given them a 99% plus accuracy rate, meaning dramatically fewer extra deliveries to rectify problems.

“We weren’t thinking about being productive,” says Barlow. “We were thinking this is wasting time, it’s wasting money.”

Research by the Industrial Strategy Council, which oversees the government’s efforts to boost productivity and wage growth, found that locally tailored policies would be more effective than top-down, big-ticket projects.

There’s also the issue of Brexit. Tougher immigration rules are designed to staunch the supply of cheaper labor from Eastern Europe, and one of the goals is to force companies to invest in technology and machinery that can reduce the need for manual workers.

But in the meantime the economy faces significant hurdles. Uncertainty over whether Brexit would happen — Britain finally left the EU on Jan. 31 after 3 ½ years of wrangling — has given way to the prospect of turmoil over trade talks. The Bank of England said in January that the limit the economy can grow without generating inflation is now just 1%.

Now there’s the impact of coronavirus, which the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development said could shrink the global economy this quarter.

“It’s easier for firms to improve productivity when demand for their product is rising, but the slowdown in the economy means that for many firms demand has been flat or even falling,” says John Young, one of the Bank of England’s network of representatives based in the northwest.

There’s also not the same money being spent everywhere. A report by the Resolution Foundation think-tank published a week before the government’s budget highlighted the stark differences in regional public investment. London’s spending per head of 1,456 pounds in 2018-19 was 53% more than in the northwest and more than double that of the East Midlands.

At the Dunsters warehouse on the outskirts of Bury, Mathew and Barlow urged the government to focus less on the new high-speed train link and do more for what’s known as “soft infrastructure” like better broadband.

“There’s probably a lot more productivity stuff that could be done without HS2, but it gets all the fanfare,” she says. “Give people the support on the ground.”

RELATED CONTENT

RELATED VIDEOS

Timely, incisive articles delivered directly to your inbox.