Visit Our Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Agnes Timbre-Sauniere’s family business near Montauban, in southwestern France, survived two world wars and more than a century of booms and busts, but the unprecedented collapse in global air travel has her worried.

The leather-printing and felt-casings enterprise started in 1905 by her great-grandfather has for decades shaped foam and stitched covers for cockpit and business-class seats for Airbus SE and other manufacturers. With COVID-19 grounding a third of planes globally, airlines have put orders on hold, crushing outfits like Timbre-Sauniere’s, which has had no new business from commercial jet seat-makers.

Her company, Celso SAS, is located a half-hour drive from Toulouse — home of Airbus and the center of European aerospace. It’s typical of the nearly 1,200 small and medium-sized aerospace-reliant entities dotting France’s southwest. Together they form the backbone of a critical supply chain for the country’s 74 billion-euro ($87 billion) aeronautics, space and defense sector that’s now struggling to cope with the fallout from the pandemic.

“Every month we lose a bit,” Timbre-Sauniere, 55, said. As head of the local chamber of commerce, she monitors the pulse of aerospace companies whose balance sheets are deteriorating. “The morale of CEOs has suffered and people are increasingly anxious about the months ahead.”

The companies and the hundreds of businesses in the area that serve them — from shops and restaurants to hairdressers and bakers — form an ecosystem that’s hanging by a thread. A deeper crisis awaits when government handouts keeping it afloat will disappear. The downturn could drag on for five years, outlasting even the most generous state support.

Similar scenarios are playing out in other European aerospace centers in the Midlands in the U.K. and around the German port city of Hamburg, where Airbus and giant equipment makers like Safran SA, Rolls-Royce Holdings Plc and Rockwell Collins Inc. seeded supply networks in an era of fast-growing air travel.

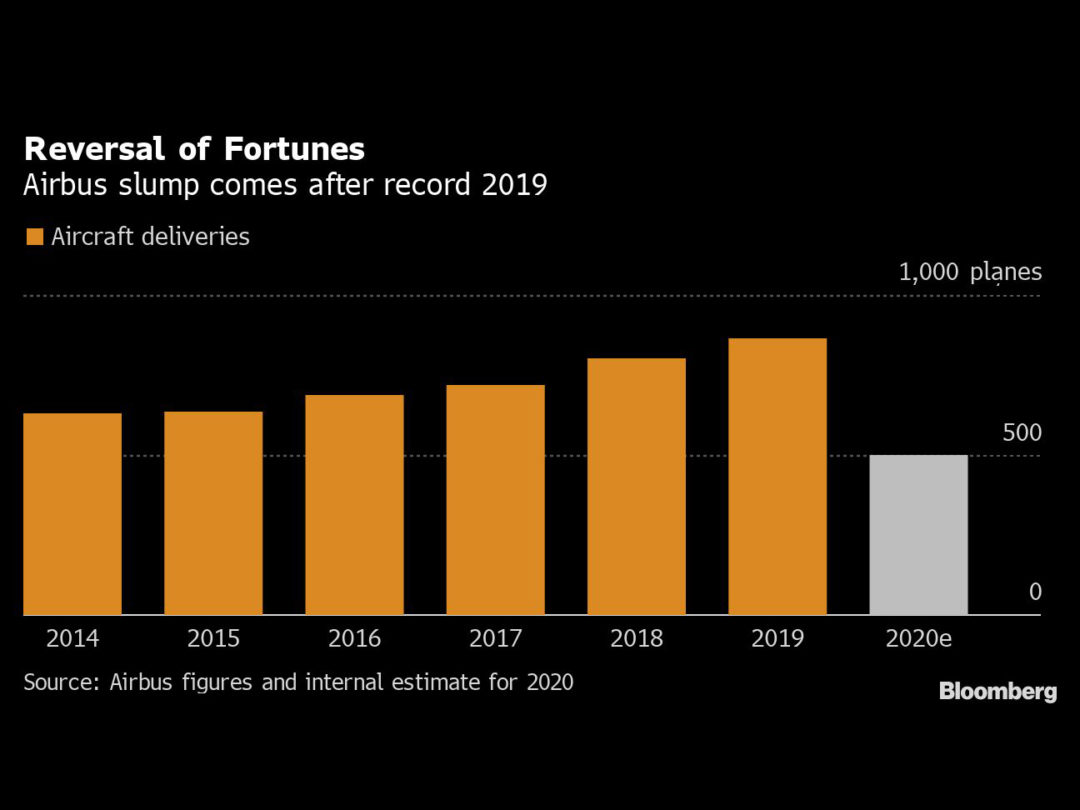

The suddenness of the downturn has been brutal. Just in January, French statistics agency Insee noted that more than two thirds of the aerospace companies in the southwest couldn’t find qualified employees. An air-travel boom had brought record deliveries for Airbus in 2019, and its assembly lines and those of its suppliers were abuzz with activity.

Then as air travel ground to a halt and plunged airlines into the red, Airbus said it was slashing production by 40% and cutting 15,000 jobs worldwide, including 5,100 in Germany — more than a third of its staff there — and about 5,000 in France, mostly in Toulouse. That set off a chain of cuts at its suppliers.

‘Too Dependent’

In the Midlands, with business drying up for Rolls-Royce, Collins and Gardner Aerospace, smaller suppliers lost up to half of their order books overnight. The region is home to a quarter of the U.K.’s aerospace industry, and without targeted state support for the sector, it’s rapidly losing jobs.

“It’s desperate, we still think we will lose 30% of people in the industry by spring next year,” said Andrew Mair, head of the Midlands Aerospace Alliance. “We’ve got some suppliers reducing their employment in half.”

Family-run firms like G&O Springs Ltd. in Redditch, a town near Birmingham, have been hit harder. It has cut staff to 23 from 50 as its aerospace work plunged by almost half.

“I don’t expect to be back to where we were till 2025,” said Managing Director Steve Boyd. “It’s going to be a long, hard slog.”

Bremen, an area near Hamburg with one of the highest unemployment rates in Germany, has been hit hard by Airbus’s job-cuts plan. State aid is masking the impact of the civil aviation industry’s meltdown on small suppliers, said Ute Buggeln, who heads the IG Metall union’s office there.

“At this point we don’t yet know how many of those smaller companies will make it,” she said. “Many of them in and around Bremen will collapse.”

But nowhere has the impact been as widespread as in the Toulouse area, where aerospace is the only game in town.

“The region is too dependent on the industry; it seems every family has someone working for Airbus,” said French lawmaker Mickael Nogal, who represents a part of the city. “We’re getting hit hard and we aren’t even close to measuring all of the fallout from the pandemic.”

For the more than 159,000 people working at companies in the southwest directly tied to the sector, hanging on to their jobs has become the biggest preoccupation.

Suppliers including Latecoere SA, Compagnie Daher SA and AAA have announced hundreds of job cuts. Without the nation’s generous state-sponsored furlough program, some 40,000 would be at risk, according to Alain Di Crescenzo, head of the Occitanie region’s business lobby. Even with the plan, about 20,000 jobs could eventually be lost, he said.

“There are some companies that will die, and we’ll have to accept that,” said Christophe Cador, chief executive of aircraft-paint specialist Satys Group, who represents smaller suppliers within France’s GIFAS lobby group.

That’s in spite of the 15 billion euros the French government has earmarked — including state-backed loans — for an industry seen as strategic. It has a job-furlough program and an investment fund to strengthen smaller companies and keep engineers working.

Before the crisis, aviation was set to expand around Toulouse, already a base for the biggest maker of turboprop planes, ATR, and business-jet manufacturer Daher. Airbus had wanted to open a new assembly line for its best-selling A320 family, while the French military chose the city for its future space command center.

All that is now on the back-burner and surviving the crisis has become job one.

That’s evident at Airbus employee watering holes like the Taverne Heidelberg, which has emptied out. Bar owner Jacques Routaboul says the coming months will be tough.

At Le Vingtieme Avenue, another popular hangout along a runway at Toulouse’s Blagnac airport, owners Stephane and Sandrine Scionico say lunch and after-hours business has shrunk by more than half. Far from gearing up for their annual Halloween-themed party, they’re thinking about shutting down.

“The situation is really dire,” said Sandrine as she surveyed the restaurant’s vast terrace, usually full of al-fresco diners and plane-spotters. “It’s bad now and I’m even more worried about what’s to come.”

RELATED CONTENT

RELATED VIDEOS

Timely, incisive articles delivered directly to your inbox.