Visit Our Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Every day, Miko Del Rosario oversees nine trucks that crisscross Southern California, weaving through alleys behind shopping malls, restaurants and a tortilla chip factory to pick up cooking oil drained from deep fryers.

The grease is filtered at his Anaheim plant to remove leftover bits of food, before it’s sold to refiners who turn it into biodiesel — a lucrative business in a state which offers generous subsidies for using scrap oils to generate fuel. But with coronavirus restrictions hurting eateries across California, Del Rosario’s daily intake has fallen 40% from before the pandemic to about 15,000 gallons a day even as orders keep coming in.

“We are maxed out right now,” he said. “If we can bring 10 more loads, they would be more than happy to take it.”

The virus-inflicted shortfall comes at a precarious time. As oil refiners face an uncertain future for fossil fuels, many are investing millions to convert refineries into renewable diesel plants that cut carbon emissions by processing discarded fats rather than crude oil. They’re now racing to secure the materials needed to feed the plants, putting some projects in jeopardy of being abandoned.

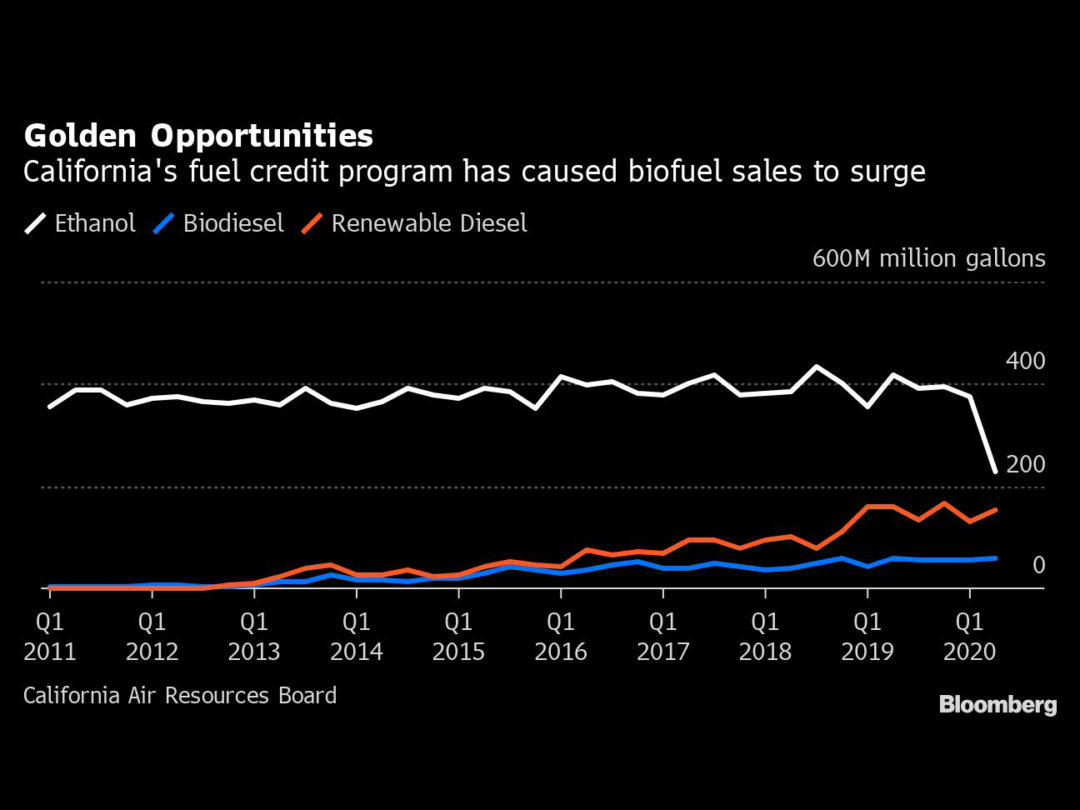

California is among the world’s biggest markets for renewable diesel in part because of a decade-old subsidy program designed to lower emissions from transport fuels. The state has more recently resolved to be greenhouse-gas neutral by 2045 and plans to phase out all gasoline-powered vehicles by 2035. Yet, even as the home of Tesla Inc. gains recognition for embracing electric vehicles, the bulk of its low-carbon fuel credits have gone to support biofuels that work in existing internal combustion engines.

The incentives have prompted U.S. refiners including Phillips 66, Marathon Petroleum Corp., HollyFrontier Corp. and Valero Energy Corp. to develop biofuel plants that run on a mixture of used cooking grease, discarded animal fat collected from slaughterhouses and oil made from soybeans and corn. At least ten projects are planned over the next few years in the U.S. alone, according to Credit Suisse Group AG.

If all of them are built, the demand for the raw materials they use could rise seven fold to about 40 billion pounds a year by 2025, equal to 93% of total U.S. supply, according to Ryan Standard, director of price reporting agency Jacobson Market Intelligence. “I don’t think there is going to be enough,” he said.

Used cooking oil and U.S. beef fat, known as tallow, accounted for 64% of the feedstock used to make renewable diesel last year in California. Those materials generate lower emissions than alternatives such as soybean oil — which require carbon-intensive farming and large swathes of land to produce — and thus receive a bigger subsidy. But unlike soybeans, which can be grown in volumes to meet demand, the supply of more valuable cooking oil and animal fat are dependent on factors not related to fuel demand.

OpenTable forecasts that one in four U.S. restaurants will go out of business as the coronavirus keeps people home, meaning a drop in used cooking oil. The dwindling supplies highlight the main risk refiners face when they switch to producing renewable diesel: having long relied on a steady supply of crude oil shipped in by pipeline or tankers, they’re now dependent on raw materials where the supply is much more out of their control.

A few hundred miles up the coast from Del Rosario, Phillips 66 is preparing to convert its San Francisco area refinery into one of the world’s largest renewable fuel plants. Operations could start as early as 2024, producing more than 680 million gallons annually of renewable diesel and gasoline, as well as sustainable jet fuel. The company is aware that securing the ingredients it needs including used cooking oil will be challenging, but with access to docks, the facility can bring in cooking oil, fats, greases and vegetable oils from around the globe, said spokesman Joe Gannon.

Entering the global market won’t be that easy. Phillips is up against experienced companies that have long established supply chains. Finland-based Neste Oyj, the world’s biggest producer of renewable diesel, already ships large amounts of U.S. beef fats to its plant in Singapore, where diesel is produced and shipped right back to California. Kern Oil and Refining Co. said in a recent filing that it plans to rely partly on tallow imported from Australia at its Bakersfield refinery. China, the world’s largest consumer market, supplied about 540,000 tonnes of used cooking oil to Europe last year, according to SCB Brokers.

At home, a few players have become increasingly important to the market. Valero Energy Corp., based in San Antonio, Texas, has a partnership with Darling Ingredients Inc. that it says provides a “large share” of the U.S. used cooking oil market. Neste recently acquired Mahoney Environmental Inc., which collects oil from 31 U.S. states.

The sooner companies can secure supplies and get their plants running, the less there will be for competitors. Some older biodiesel plants will probably close as the new renewable diesel plants start operating, said John Jansen, vice president of oil strategy at United Soybean Board. “I don’t think it was happenstance that all these facilities announced at the same time,” Jansen said, as they try to discourage others from pushing ahead with their projects.

Prices are already rising as supply gets tighter, squeezing refiners’ profit margins. Including inflation, the cost of tallow is set to rise by about 20% in the next five years, while used cooking oil will become 16% more expensive, according to data from Stratas Advisors. In Rotterdam, where a large share of Europe’s biodiesel is produced, used cooking oil prices are about 15% higher than they were a year ago, SCB Brokers data showed.

The race to secure feedstocks for renewable diesel plants has already taken casualties. In May, New Zealand’s Z Energy Ltd. shut a biodiesel plant after an overseas bidder drove up the cost of domestic tallow, used to make fuel for the U.S. market, local media reported.

“Basically this means that small-scale, inefficient waste-based biodiesel producers will have most difficulties staying in business,” said Marijn Van der Wal, biofuel manager at Stratas Advisors. “They can’t afford to pay as much as the big renewable diesel players do.”

RELATED CONTENT

RELATED VIDEOS

Timely, incisive articles delivered directly to your inbox.