Visit Our Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

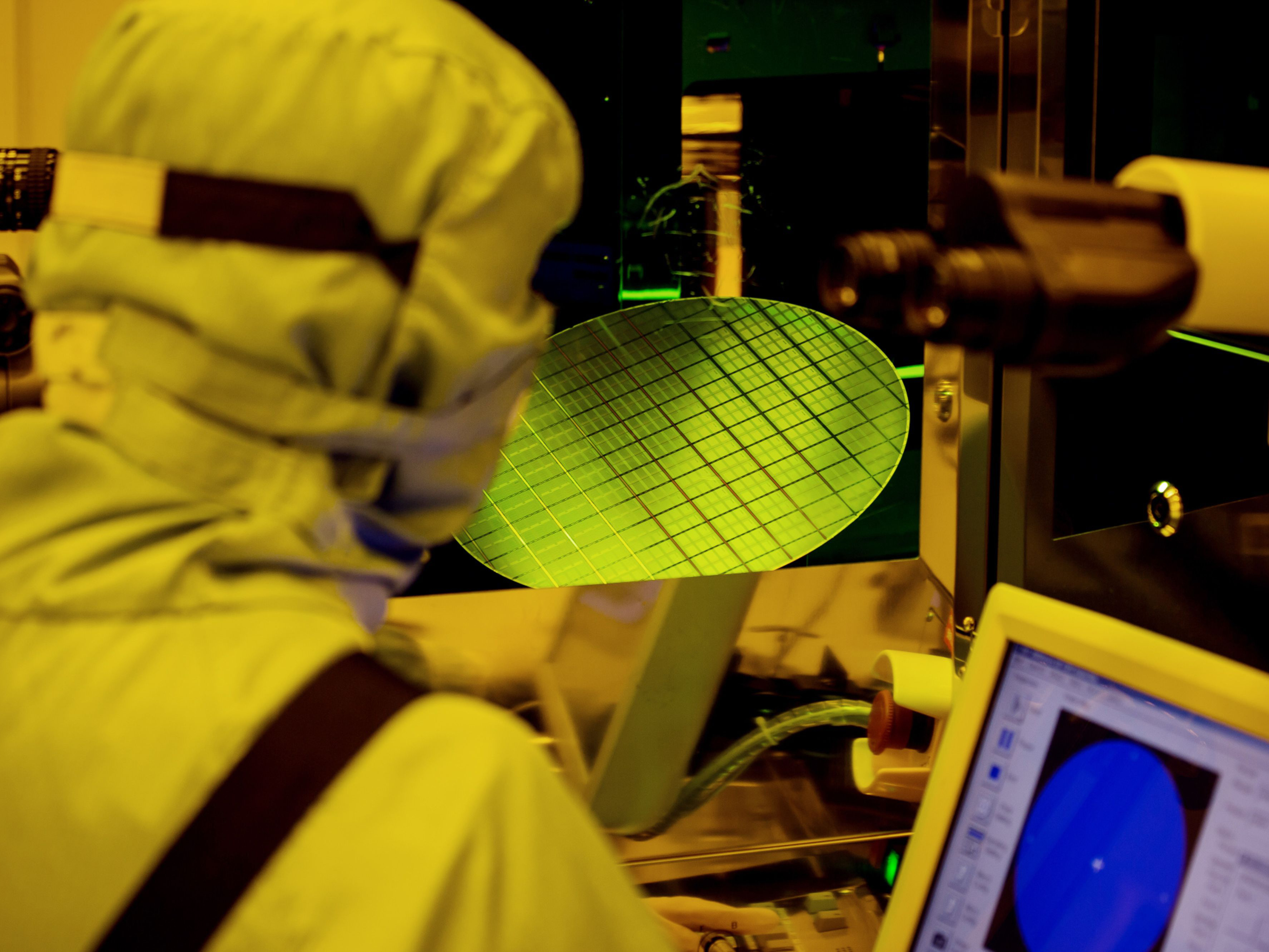

The European Union unveiled its plan Tuesday to use its economic leverage to attract large semiconductor producers like Intel Corp. and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., but reaching the full 45 billion euro ($51.4 billion) price tag depends on a controversial and untested method of subsidizing production.

Under the EU’s Chips Act, the bloc would allow its massive state aid funding program to be used for “first-of-a-kind” production sites in Europe, as part of a larger goal of producing 20% of the world’s semiconductors by 2030.

Despite broad agreement over the need to address the global chip shortage, the EU plan could face significant hurdles — both over its direct funding, which relies on already allocated money and stretched EU government budgets, and its use of state aid, which some countries and EU officials worry could lead to a subsidy race.

“Europe needs advanced production facilities, which come, of course, with a huge upfront cost,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said Tuesday in Brussels. “We are therefore adapting our state aid rules, of course, under strict conditions, and this will allow for the first time public support for European first of a kind production facilities.”

The EU’s Chips Act aims to put the bloc on the same playing field as the U.S., which has proposed a competing $52 billion plan. Overall, the EU executive arm’s plan would be backed by roughly 45 billion euros in public and private money. About 15 billion euros will be part of a public-private partnership for research and innovation, with another 30 billion euros in state aid aimed at chip production and smaller projects.

Previously, the EU only allowed state aid for research and the first production run, but the commission tweaked its rules to allow subsidies for semiconductor manufacturing — a change that may prove controversial inside the bloc.

Companies’ requests for subsidies are likely to face tough scrutiny from the commission’s competition department, as they have to prove their plans are truly first of a kind in Europe and there is a genuine funding gap. The commission’s competition chief, Margrethe Vestager, said in a news conference that state aid will be “targeted and proportionate.” She added, “Only what is needed and nothing more.”

Vestager also pushed back against the idea that the first-of-a-kind criteria constituted a change to state aid rules. “We’re not bending, we’re not adapting the state aid rules,” she said. “We’re using the provision of a treaty that allows to enable economic activity. That is in the treaty.”

The rest of the money backing the proposal isn’t guaranteed either, as the EU is reallocating more than 5 billion euros that's already been distributed in the EU budget and could face opposition from EU countries and the European Parliament. The Chips Act runs until 2030, and with the current EU budget ending in 2027, the commission earmarked more than 1 billion in the next EU budget, a plan that could be nixed when the next commission takes office.

The vast majority of the money will come from EU countries, which is expected to have more than 100 smaller projects under the Important Projects of Common European Interest program, and could make billions available in state subsidies.

The EU plans more oversight for semiconductor companies to ensure the security of supply. If there is a crisis, countries would be able to require companies to report stock levels, prioritize certain orders and jointly purchase items.

The measures unveiled Tuesday left some industry groups saying the details were still insufficient.

“It is still unclear how much indirect funding (money coming from member states) will be secured, and how it will be spent,” DigitalEurope, an industry group, said in a statement. “More clarity on the size and source of funding especially for research and development is needed.”

Even so, companies largely welcomed the EU’s overall proposal, with Infineon Technologies AG CEO Reinhard Ploss writing in a statement that it is “an important step towards establishing a semiconductor ecosystem in Europe at the top global level and reducing unilateral dependencies.”

Intel also pushed the EU to work with the U.S. “for the sake of our collective economic stability and supply chain security,” especially by aligning regulation in the joint Trade and Technology Council.

RELATED CONTENT

RELATED VIDEOS

Timely, incisive articles delivered directly to your inbox.