.jpg?height=100&t=1742184082&width=150)

Visit Our Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Montana’s vast spaces and epic vistas, its mountains and boundless plains, seem made for a road trip. Just not in an electric car.

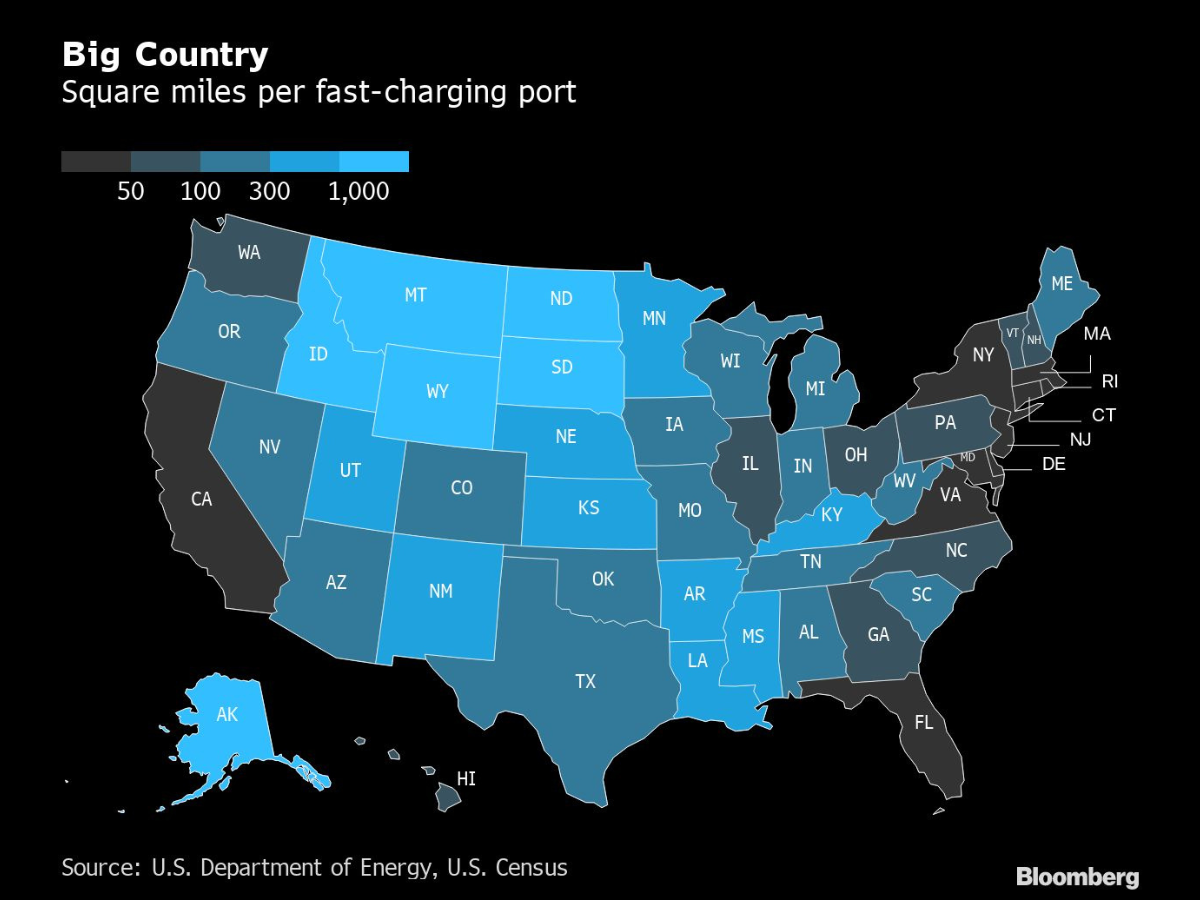

There’s almost no place in public to plug in. Across Montana’s 147,000 square miles, the state government recently counted 57 charging stations, most of them clustered in towns and cities rather than along the highway. Traveling the long stretches between communities requires careful planning, or leaving the EV at home.

“You have to get your map out,” said Bozeman resident Nick Shrauger. “It’s an adventure. It isn’t easy.”

Shrauger’s go-to car for errands is his 2017 Chevrolet Bolt, one of only 1,650 electric vehicles registered in the state. He’ll even use it to lug tanks of diesel fuel from the gas station to the tractors on his small, hay-growing ranch. But when he hits Montana’s wide-open roads, Shrauger often drives his gas-powered Toyota Highlander instead. Taking the Bolt means plotting a route around friends’ homes and RV campsites where he can plug in and sneak a few miles of range.

“I struggle to put 8,000 miles a year on it, because of the lack of charging,” said Shrauger, 86, a retired electrical engineering professor from Montana State University.

It’s exactly the problem U.S. President Joe Biden wants to fix.

Eager to lure Americans from their gas-burning cars, Biden’s administration is planning a nationwide network of 500,000 charging stations linking urban and rural areas coast to coast. Last year’s infrastructure law set aside $5 billion to build it. Along interstate highways and other major roads, the feds want a station every 50 miles, with at least four charging ports apiece — ones that will add electrons relatively quickly. States, which will play a major role in deciding where those chargers go, face an Aug. 1 deadline to tell the federal government how they would like to spend the money. Each state’s share of the funding, slated for distribution starting this fall, will be equal to their portion of annual federal highway spending.

It’s hard to overstate how much Biden’s climate fight relies on EVs. The Supreme Court has limited the federal government’s ability to regulate greenhouse gases, and tax breaks to spur low-carbon technologies have been stalled in the Senate. Key senators said this week that they finally reached a deal on them, but passage by a deeply divided Congress is not guaranteed. The shift from internal combustion engines to electric cars is one of the biggest carbon-cutting options open to the president. But it requires convincing millions of drivers to take the plunge — something they won’t do if they’re worried about running out of power on the road. It’s a chicken-and-egg conundrum that has largely left rural America out of the electric-vehicle revolution.

“What does it take to tip people who are considering buying an EV into buying it?” said Jonathan Levy, chief commercial officer of charging company EVgo Inc. “The infrastructure, the visibility of it, and the existence of it will help.”

This enormous undertaking carries risks. Ensuring drivers won’t get stranded in the middle of nowhere means planting some stations in remote locales where they’ll get little use for years. Montana’s own report on building out the network warns some stations could see fewer than 10 charging sessions per month. Those stations’ owners will lose money until EVs represent a sizable chunk of cars on the road, and those chargers will still need maintenance to make sure they keep working in all kinds of weather.

“You have high-powered, super high-tech, connected equipment out there exposed to the elements,” said Michael Farkas, chief executive officer of Blink Charging Co. “It’s not like a pay phone you can just put out there.”

That calculus is itself a reason for the government push. Companies such as Blink, EVgo, ChargePoint Holdings Inc. and Electrify America LLC have been deploying chargers for years, and are increasingly working with big automakers like General Motors Co. and Ford Motor Co. to accelerate the effort. But they’ve focused on the urban and suburban areas that were first to embrace EVs, and generally look for sites with the biggest profit potential, leaving many American highways uncovered.

“We believe it’s important to invest in some of those locations where we know we aren’t going to see private investment for quite some time,” said Kyla Maki, an energy resource professional with Montana’s Department of Environmental Quality. She points to a road that locals call the “Hi-Line” — U.S. Highway 2, along the northern border — which is a remote but a key route for Canadian tourists. “Highway 2 is one of those corridors where it’s tough to see any private company coming in in five years, maybe not even in seven years,” she said.

The Biden administration’s effort is being overseen by two federal agencies — the departments of energy and transportation — as well as a joint office involving both. They declined to make officials in the program available for an interview. The infrastructure law also set aside $2.5 billion for more community-focused charging projects, with the money to be awarded to states on a competitive basis.

The federal government has tried rolling out chargers before, at a smaller scale and without great success. President Barack Obama made EV charging part of his economic recovery plan after the Great Recession, awarding $100 million in 2009 to Ecotality Inc. of San Francisco to deploy residential, commercial and public chargers in five metropolitan areas across the country and analyze their use. The public fast-chargers were supposed to be installed every 10 miles along major roads, but so few people were buying EVs at the time that the government significantly scaled back the initiative. Ecotality filed for bankruptcy in 2013.

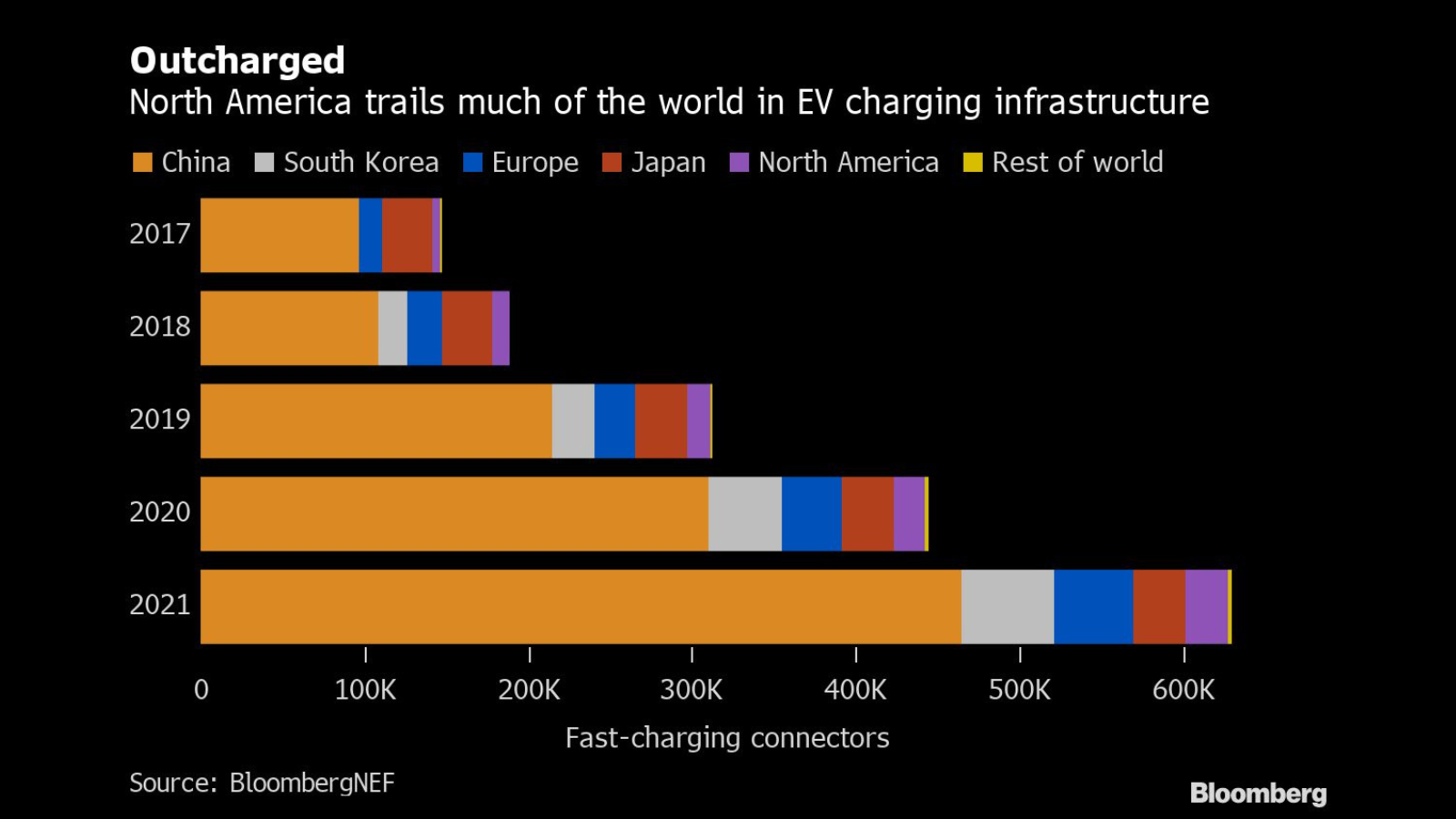

In the years since, the U.S. has fallen well behind Europe and China in building out its network. A BloombergNEF analysis counted 112,900 public chargers deployed across the U.S. by the end of 2021, compared with 442,000 in Europe and 1.15 million in China. That gap is growing, with just 23,725 U.S. chargers installed last year, versus 95,000 in Europe and 337,100 in China. China’s command-control economy makes the EV rollout there quite different, while Europe lacks the big rural spaces that Biden’s team must tackle. European drivers have also been quicker to buy electric vehicles, so there’s less risk of underused chargers.

“Europe is installing to keep up with the market — you’re trying to meet demand that already exists,” said Ryan Fisher, lead analyst of EV charging for BNEF. “In America, you’re trying to meet demand that doesn’t yet exist.”

Tesla Inc. proved that a U.S. charging network can work, at least for its own cars. Some of the only fast-charging stations in Montana are Tesla’s, strung along interstates 90, 94 and 15. But for now, only Tesla drivers can use them (although the White House has suggested that may change, and Tesla has been experimenting with letting non-Tesla drivers use superchargers at select stations in Europe). Bozeman has four Tesla Superchargers at a Hilton hotel, but they are of no use to Bolt pilots like Shrauger. When they need to top off in public, they use the plugs at the local Audi dealership instead.

For the other charging companies, who will be bidding on the state contracts for EV stations, there isn’t a clear-cut model to follow. There’s wide agreement that fast-charging stations will be needed along rural highways, and the federal government has proposed requiring them for its $5 billion network. But some of the companies argue that slower and cheaper chargers can still play a role, particularly in more populated areas and among apartment dwellers without driveways and garages.

Local conditions will make a big difference. Putting a station at a suburban grocery store, for example, might appear to make sense, since there will be plenty of cars parked there on a regular basis. But most suburban drivers will have chargers at home and won’t actually need to plug in while shopping.

“To put a charging station in the middle of suburbia, where it’s not along a travel corridor and there’s single-family homes for miles in each direction, that is a money-loser,” Farkas said. “There are going to be a lot of white elephants out there.”

On the open highway, chargers will be deployed at gas stations, restaurants or other amenities just off the freeway, rather than standing alone in a roadside pull-off — the result of a decades-old federal law limiting commerce at interstate rest stops. Ideally, they will be where travelers already stop to stretch their legs, grab food and hit a restroom, said Pasquale Romano, chief executive officer of ChargePoint. “There’s reasonable security, there’s care and feeding of the equipment past when the funding runs out — there’s a business that cares,” he said. “For a long period of time, businesses are going to want to serve both electric and liquid fuel.”

That model is already emerging. This month, GM announced it would work with EVgo to install chargers at up to 500 Pilot and Flying J travel centers, which offer food and fuel. In Montana, local company Town Pump, which runs travel centers, hotels and casinos, is installing chargers in 14 locations with money the state received from Volkswagen for cheating on auto emissions tests.

Building from that base will take planning. Some rural areas may need to upgrade the local power grid — the transformers and substations feeding remote power lines — to accommodate multiple cars charging at the same time.

“To put four chargers there, that’s one thing, but as you grow and add chargers, that could be a problem for the grid,” said Rob Stapley, rail, transit and planning division administrator with the Montana Department of Transportation.

Then there’s the requirement that charging stations be no more than 50 miles apart. In heavily populated areas, that seems simple. In much of the Great Plains and the West, however, it doesn’t match local reality.

“We have stretches where it’s more than 50 miles between gas stations,” Stapley said. “So that does not seem reasonable.”

Wyoming, for example, is seeking an exception to that rule, in part because it is concerned federally subsidized stations will wipe out the profit of the few chargers it already has. The state also wants to use the money to buy portable charging equipment that can be fitted to a roadside emergency vehicle.

Montana’s plans for the network focus on first ensuring there’s a charger every 100 miles, then filling in from there. State officials want maximum flexibility from the federal government on that, as well as buy-America rules that they fear could block most charging equipment available today.

“We’ve been told that you cannot acquire a charger that meets the buy-American standard currently,” Stapley said. “That’s a big hurdle to overcome.”

The federal government will allow exceptions to the 50-mile requirement, but states have to apply for them on a case-by-case basis. And they need to show that meeting the rule will either be prohibitively expensive in some locales, would require major upgrades to the power grid, or that there aren’t sites with good access and amenities in the places in question. As for buying American-made equipment, the Department of Transportation says it’s taking feedback on the requirement and working to establish guidance.

Montana stands to get about $43 million of the federal infrastructure funds over the next five years. In year one, it plans to build 10 charging stations to shrink its largest electron deserts. One of the first is plotted for Columbus, 101 miles straight east of the Audi dealership in Bozeman. Shrauger, for one, is looking forward to it. “I saw a fuel truck at the gas station the other day,” he said, “and I was joking around with the driver, telling him ‘I might put you guys out of business.’”

RELATED CONTENT

RELATED VIDEOS

Timely, incisive articles delivered directly to your inbox.

.jpg?height=100&t=1742184082&width=150)