Visit Our Sponsors |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Come next summer, at a lithium-ion battery factory in Endicott, N.Y., thousands of rechargeable cells should start rolling off a production line. Run by Imperium3 New York LLC, a consortium of small companies, it will be the only new production facility of its type to open in 2021 in the U.S., delivering batteries to clients in defense, transportation, and other industries.

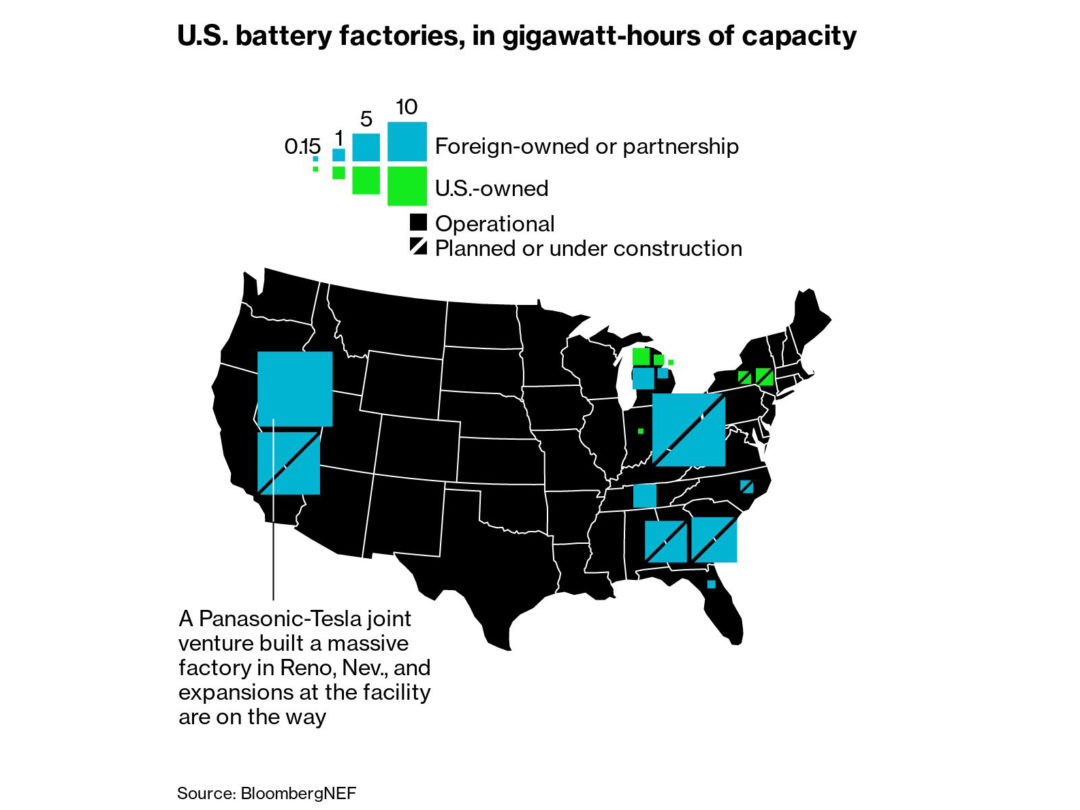

With an initial annual output of cells equal to 1 gigawatt-hour — enough to power about 19,000 electric vehicles at the current average pack size — the capacity at Endicott is a fraction of what global rivals will produce. China and Europe will respectively add about 40 and 19 times that volume next year, BlooombergNEF estimates.

For all it represents — energy efficiency, technological advancement, the future of manufacturing — the Imperium3 plant and its projected output also reflect that the U.S. is falling further behind in the battery race.

The global battery market to power EVs and consumer electronics and to store renewable energy on power grids will be worth about $116 billion a year by 2030, BloombergNEF forecasts, up from around $28 billion now. The U.S. is on course to capture only a small piece of that. “I’m dumbfounded,” says Frank Poullas, executive chairman of Magnis Energy Technologies Ltd., one of the Endicott factory’s owners. “There’s so much activity in Europe and in Asia, and then in the U.S. it’s almost nothing.”

American and German automakers dominated the 20th century, pioneering and continually improving the internal-combustion engine. Japan and China, which industrialized later, were left to play catch-up. But now Asia — led by China and South Korea — leads the way in developing cheap, powerful technology for the EV era.

U.S. industries will suffer if rising battery demand is met only by foreign companies, experts say, and job losses in the already shrinking auto sector will be even greater if cell production is concentrated overseas. “The U.S. could actually lose out on a lot of the economic opportunities, while Europe and Asia start to take control,” says David Deak, an operating partner in Azimuth Capital Management who’s focused on low-carbon energy investments.

There are national security implications, too, for the U.S. and others from a battery supply chain dominated by China, a nation capable of wielding exports as a political tool. By 2025, China will have battery facilities with maximum production capacity of about 1.1 terawatt-hours’ worth of cells a year, almost double the rest of the world combined.

The White House response has so far been inertia, a shift from the U.S. posture after the 2008-09 financial crisis, according to Cathy Zoi, chief executive officer of charging-network operator EVgo Services LLC. As an assistant secretary at the U.S. Department of Energy under President Obama, Zoi was among the officials who distributed public funds to build American battery factories for hybrid vehicles. Stimulating the sector again will help the U.S. auto industry, she says. “There’s a giant opportunity.”

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other European leaders understand this, and the continent will lead the U.S. in manufacturing capacity beginning next year. The European Union will spend €500 billion ($590 billion), about a third of its seven-year budget, on green technology that’s likely to include batteries.

What’s not clear is whether European battery production will come mainly from satellite factories run by established Asian giants or from homegrown European players.

“Considering the battery represents 40% of the value of an electric car, the difference between those two scenarios is huge,” says Peter Carlsson, CEO of Northvolt AB, which is building a production facility in northern Sweden and planning a second with Volkswagen AG in Germany. Founded by two former Tesla Inc. executives, the company will likely benefit from Europe’s green push. It raised $1.6 billion in debt in July and received $525 million in loan guarantees from Germany in August.

As they build out electric assembly lines, the continent’s automakers want suppliers close by, to prevent disruption, Carlsson says, and “from a political perspective, to secure the jobs of the future.” That’s a reaction to moves by several battery suppliers, including China’s Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., which is building its first overseas plant in Germany.

Chairman Zeng Yuqun says CATL is eyeing expansion in the U.S., but its less-developed network of suppliers is an obstacle. That hasn’t stopped its South Korean rivals: LG Chem is adding capacity in Ohio, and SK Innovation Co., which is also building in Hungary, expects a plant in Commerce, Ga., to begin production in early 2022.

China’s grip extends to almost every component within the battery: It accounts for about 80% of the chemical refining that converts lithium, cobalt, and other raw materials into ingredients, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, an industry adviser. “Other nations, especially China, are consolidating control of the supply chains for the minerals that form the foundation of modern society,” says Senator Lisa Murkowski, the Alaska Republican who chairs the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. “By ceding that control, we are losing out on jobs and growth. That will only worsen as emerging industries like advanced batteries and electric vehicles take hold.”

Some alliances are being formed to help push China back. Automakers including General Motors Co. and PSA Group have entered into battery-producing joint ventures with vendors from South Korea and Europe. Still, Volkswagen, Daimler AG, and other brands are investing directly in China’s manufacturers to guarantee future supplies.

A degree of caution in the U.S. is understandable. EV adoption is happening at a slower rate — European EV sales have substantially exceeded those of the U.S. in all but two quarters in the past four years. With the pandemic slowing global auto purchases, battery sales are forecast to drop for the first time in three decades. Stimulus programs elsewhere aim to support the rollout of EVs. There’s no such move from the U.S. government, though Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden has indicated the sector could get a boost if he’s elected.

Some are optimistic that the U.S. eventually will catch up. Incentives to foster local production of components like battery electrodes would spur investment in everything from mines to complex manufacturing, Azimuth’s Deak says. And growing EV production will ultimately require regional supply chains.

“The same thing will happen in the U.S.,” Deak says. “It’ll just take longer and happen a little slower.”

RELATED CONTENT

RELATED VIDEOS

Timely, incisive articles delivered directly to your inbox.